Evidence-Based Curriculum

‘Evidence-based practice’ means a practice or treatment, or set of tools, “that has been scientifically tested, subjected to experts of clinical judgment, and determined to be appropriate for the intervention or treatment of a given individual, population, or problem area.”

Evidence-based practices are developed, implemented, further researched, and refined over time and therefore build more evidence regarding their reliability and effectiveness.

Evidence-based practices are important because they help ensure decisions about assessments, tools, and curriculum are based on strong research rather than assumptions, historical use, or opinions.

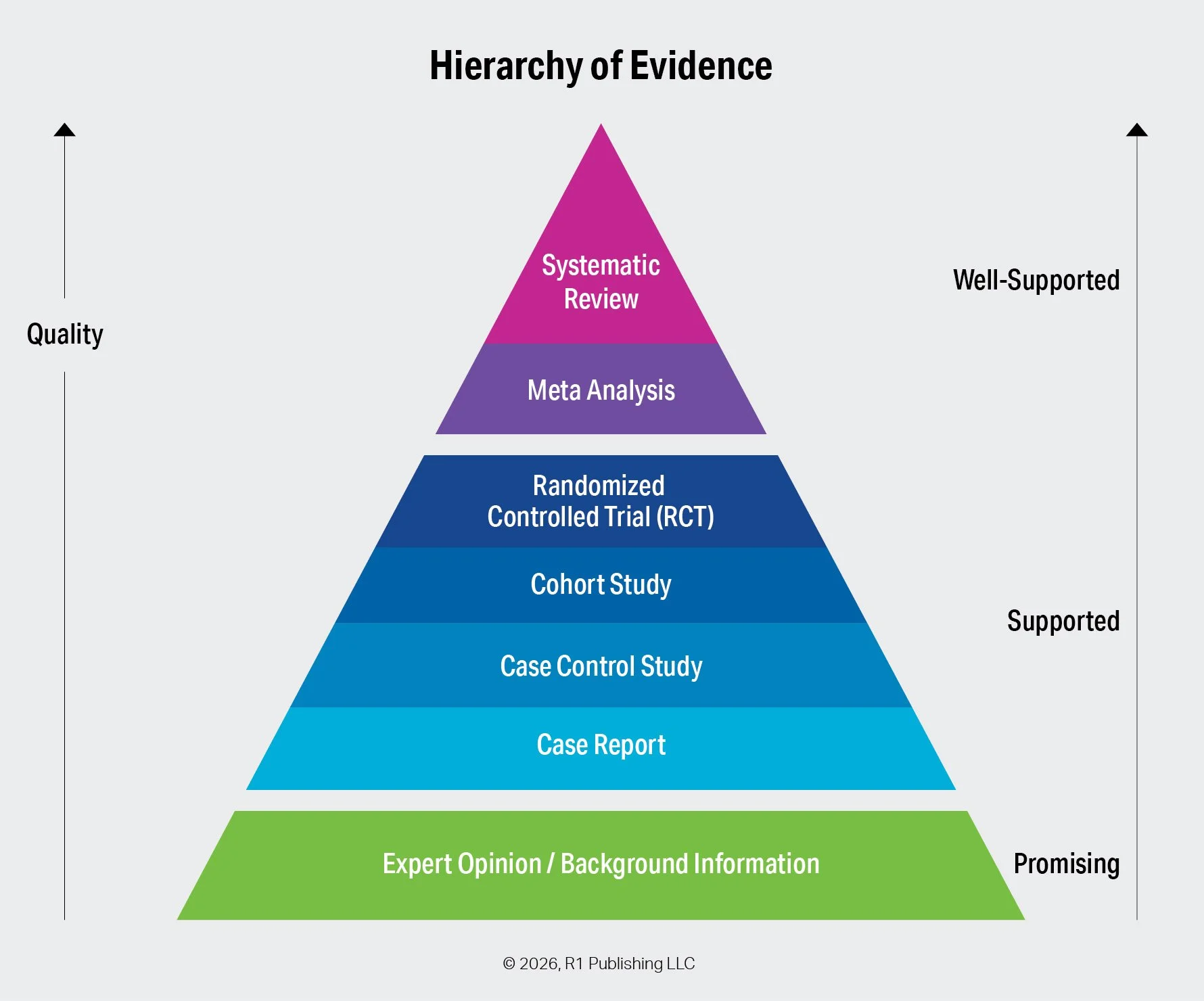

The Hierarchy of Evidence is a way of ranking different types of information based on how reliable, trustworthy, and effective they are. Some types of evidence are stronger because they use careful methods, large amounts of data, and reduce bias, while others are weaker because they rely on small samples, observation, or opinion.

This hierarchy is important because it helps providers, programs, and practitioners make better decisions on what and how to implement interventions, curriculum, and tools depending on their populations and settings. By understanding which evidence is stronger, researchers, clinicians, and policymakers can place more confidence in conclusions that are based on high-quality studies and be more cautious with weaker evidence. In simple terms, it helps one separate what is most likely to be true and most effective from what is less reliable.

As organizations, providers, programs, and practitioners are selecting the best curriculum and tools for their population and setting, the question is not just “is your curriculum evidence-based”, but “where are you on the hierarchy”.

The Hierarchy of Evidence: Types and Categories

Let’s start with the basics. The primary types of evidence include the following, listed from highest to lowest strength:

Systematic Review – A systematic review comprehensively collects, evaluates, and synthesizes all relevant research on a specific practice, treatment, or intervention. Because it applies rigorous methods and critically appraises its sources, it is consistently ranked at the top of the evidence hierarchy.

Meta-Analysis – Often conducted as part of a systematic review, a meta-analysis statistically combines data from multiple studies. By aggregating results, it increases statistical power and produces conclusions that are more robust than those of individual studies. Its data-driven nature also helps reduce bias compared to purely observational research.

Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) – RCTs are structured experiments in which participants are randomly assigned to receive one of two or more interventions. Randomization minimizes selection bias and other sources of error. Although often placed just below systematic reviews and meta-analyses, some hierarchies rank RCTs at the highest level.

Cohort Study – A cohort study is an observational design in which researchers follow a group of participants who share a common characteristic and compare outcomes with a group that does not share that characteristic. Researchers observe outcomes without intervening.

Case-Control Study – In a case-control study, researchers compare individuals who have experienced a specific outcome (cases) with those who have not (controls). The groups are examined for prior exposure to potential risk factors. A higher exposure rate among cases suggests an association.

Case Report – A case report provides a detailed description of a single patient or a small group, including symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes. While considered lower-quality evidence due to limited sample size, case reports often serve as early indicators of emerging practices or effects.

Expert Opinion and Background Information – At the base of the evidence hierarchy are expert opinions and background sources. This category typically reflects professional consensus or guidelines issued by authoritative organizations rather than the views of a single individual.

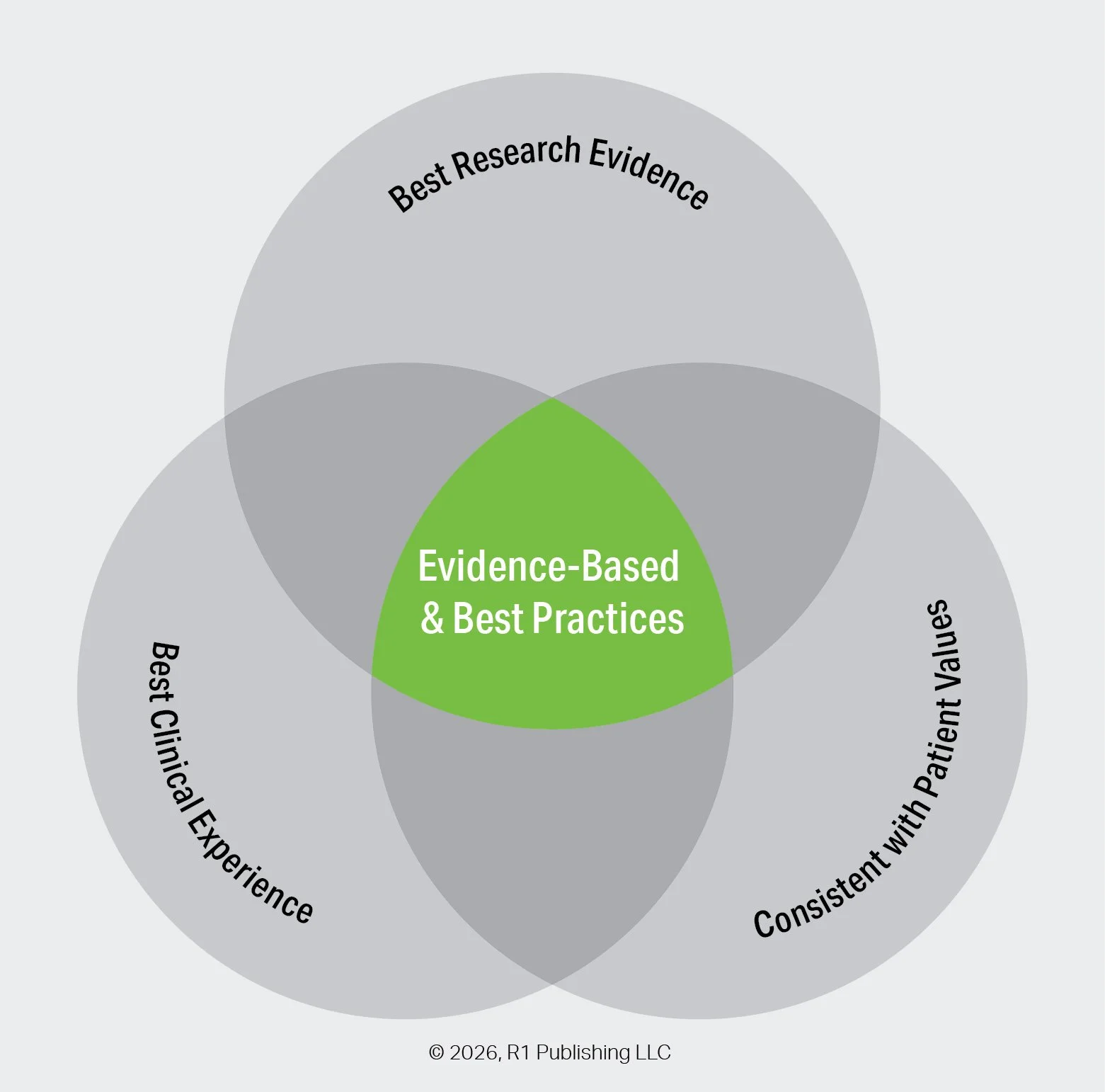

Evidence-based and best practices occur at the intersection of three equal considerations:

Best research evidence provides reliable findings from high-quality studies to inform what works.

Best clinical experience brings professional judgment and practical expertise gained through real-world practice.

Consistency with patient values ensures that decisions respect individual preferences, needs, and goals.

When these three elements are considered together, practices are more effective, appropriate, and meaningful.

The R1 Learning System and curriculum are derived from the best research evidence and constructed with flexibility to allow practitioners to adapt them to their role, knowledge, skill, experience, and specific considerations of their populations and settings. Below you will find a selection of research evidence in several core areas.

Evidence-Based Practices

What are 16 of the most widely recognized evidence-based practices and how does R1 enhance them?

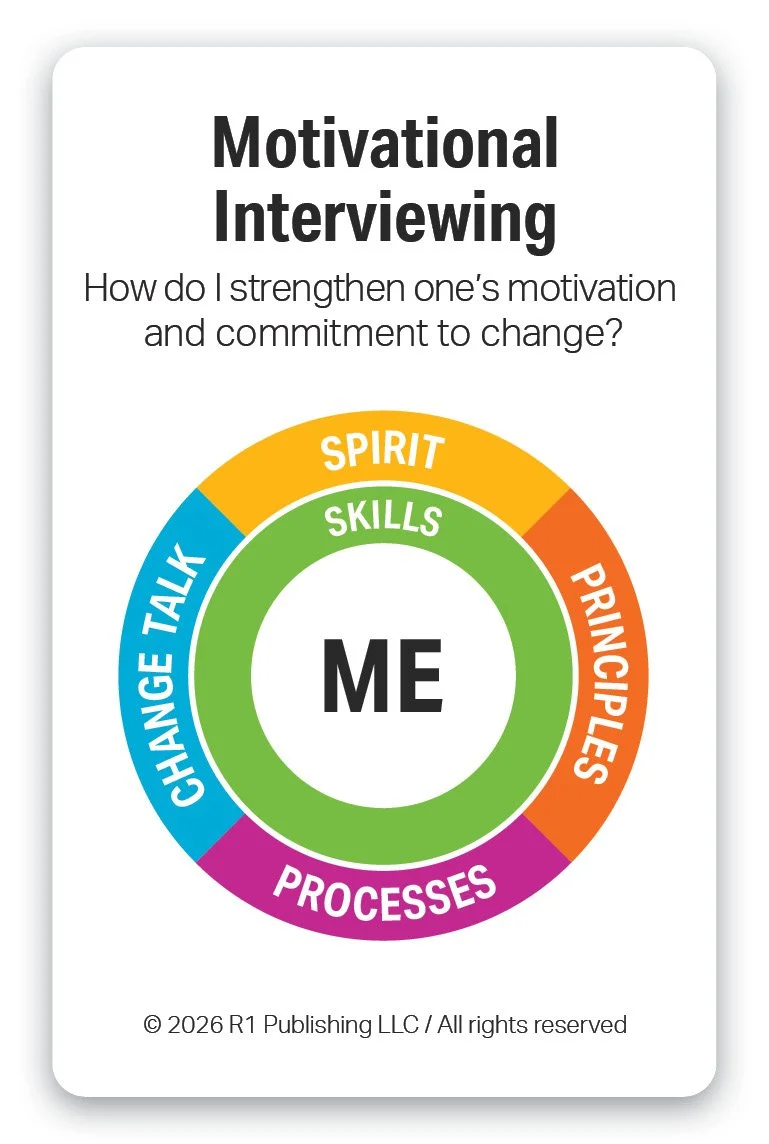

Motivational Interviewing (MI) is a collaborative, person-centered evidence-based approach designed to strengthen an individual’s motivation and commitment to change. It focuses on exploring and resolving ambivalence rather than persuading or directing. Through open-ended questions, reflective listening, and affirmation, MI helps individuals articulate their reasons for change. Its purpose is to support autonomy and empower individuals to make meaningful, self-directed behavior change.

R1 enhances MI by enabling individuals to learn about themselves through a reflective self-discovery process and find relevant and meaningful insights specific to their situations and circumstances. This resulting concrete information provides a foundation when using MI. Practitioners can use any of the R1 topic activities to set the stage for MI in both group and 1-on-1 settings. Any Discovery Card selected can be used as a focused meaningful prompt for engaging and individual using MI. Link to MI Skills Worksheet.

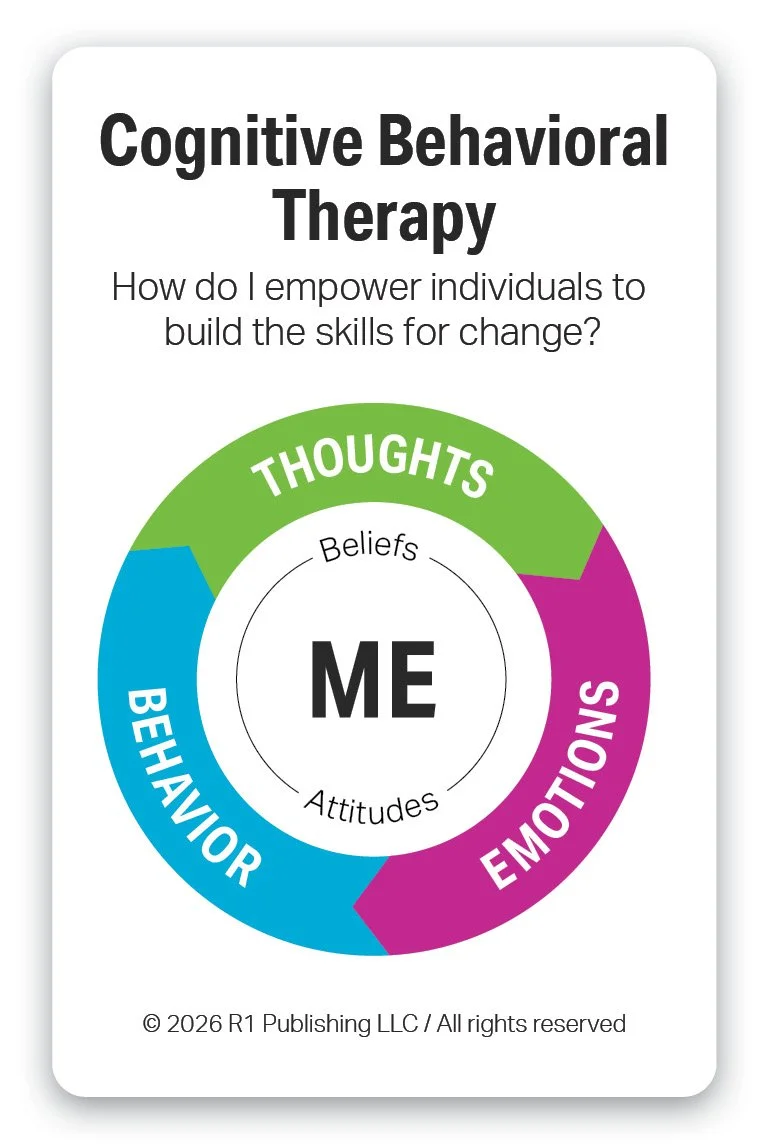

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is a structured, evidence-based form of psychotherapy that focuses on the connection between thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. CBT helps individuals identify and challenge unhelpful thinking patterns and replace them with more realistic and constructive ones. By practicing new skills and behaviors, individuals learn healthier ways to respond to challenges. The purpose of CBT is to reduce psychological distress and improve functioning by promoting lasting, practical changes in thinking and behavior.

R1 enhances CBT by enabling individuals to self-discover their patterns of thinking, emotions, and behavior using concrete tools. R1 topics such as Emotional Triggers and Substance Use Warning Signs use a CBT framework for learning and goal setting. Link to CBT Skills Worksheet.

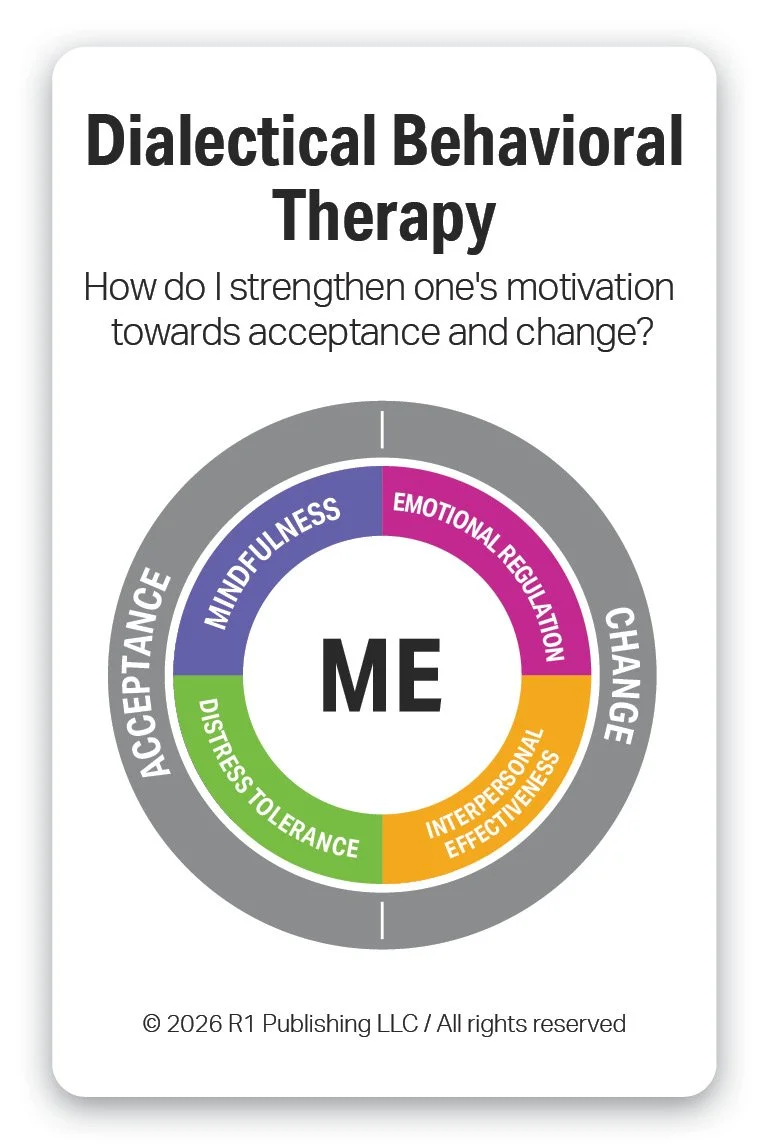

Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) is an evidence-based form of psychotherapy that combines cognitive-behavioral techniques with mindfulness and acceptance strategies. It focuses on helping individuals manage intense emotions, reduce self-destructive behaviors, and improve relationships. DBT teaches practical skills in mindfulness, distress tolerance, emotion regulation, and interpersonal effectiveness. Its purpose is to support emotional stability and build a life worth living through balanced acceptance and change.

R1 enhances DBT by increasing the vocabulary for individuals in topics like Emotional Triggers, Emotions & Feelings, and Emotional Regulation Practices (Coming 2026). R1 topics for Life Skills, Communication Skills, Problem Solving Skills (Coming 2026), Prosocial Skills (Coming 2026), and Mindfulness Practices (Coming 2026) provide increased knowledge, self-awareness, and a foundation for more effective engagement for DBT.

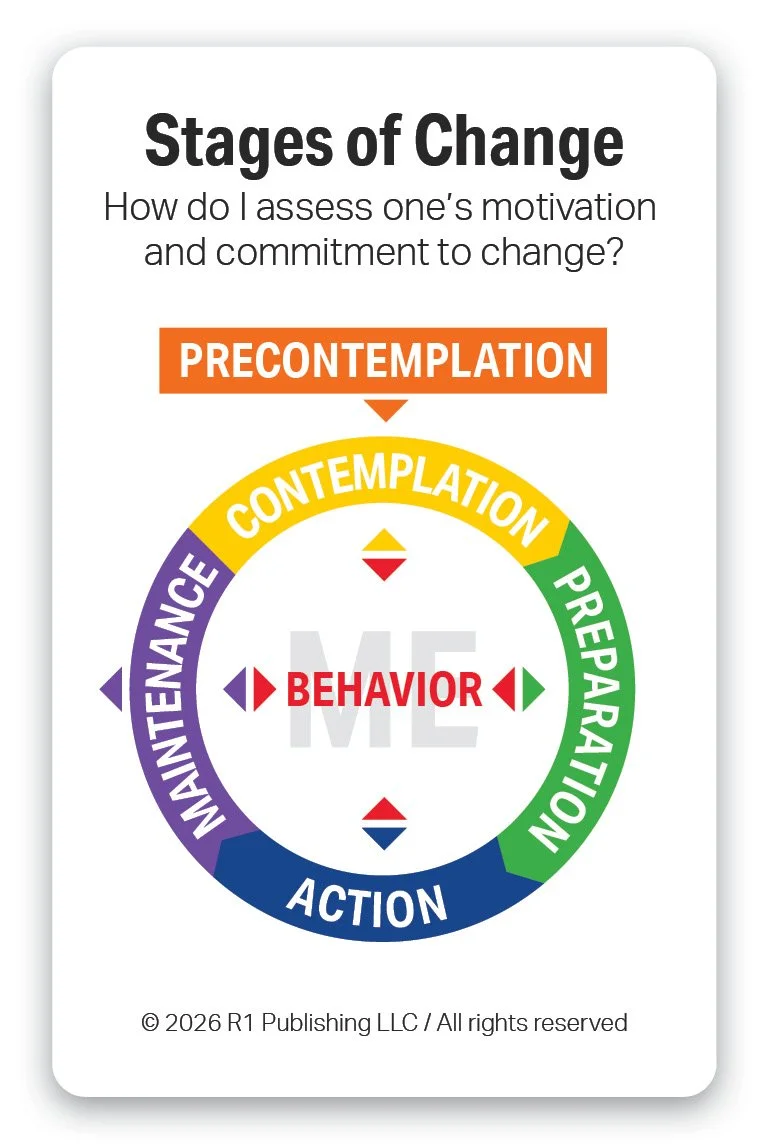

The Stages of Change, or Transtheoretical Model, is an evidence-based framework that outlines the cyclical, six-stage process—precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, maintenance, and recurrence of use —individuals pass through when modifying behavior. Developed by Prochaska and DiClemente, its purpose is to guide individuals from being unaware of a problem to sustaining long-term behavioral changes, such as in addiction recovery or health improvement. By assessing an individual’s current readiness to change, this model enables professionals to provide targeted, personalized interventions that enhance motivation and reduce resistance.

R1 enhances the Stages of Change by providing two versions of our Discovery Cards, Facilitator Guides, videos, and R1 Discover App interactivities, one for substance use and another for assessing any behavior. These tools enable individuals to reflect, observe, and evaluate which stage they think they are in based on evaluation of concrete behaviors. Furthermore, the R1 Learning System’s behavioral-based Discovery Cards decks can apply these Stages of Change evaluations across multiple topics.

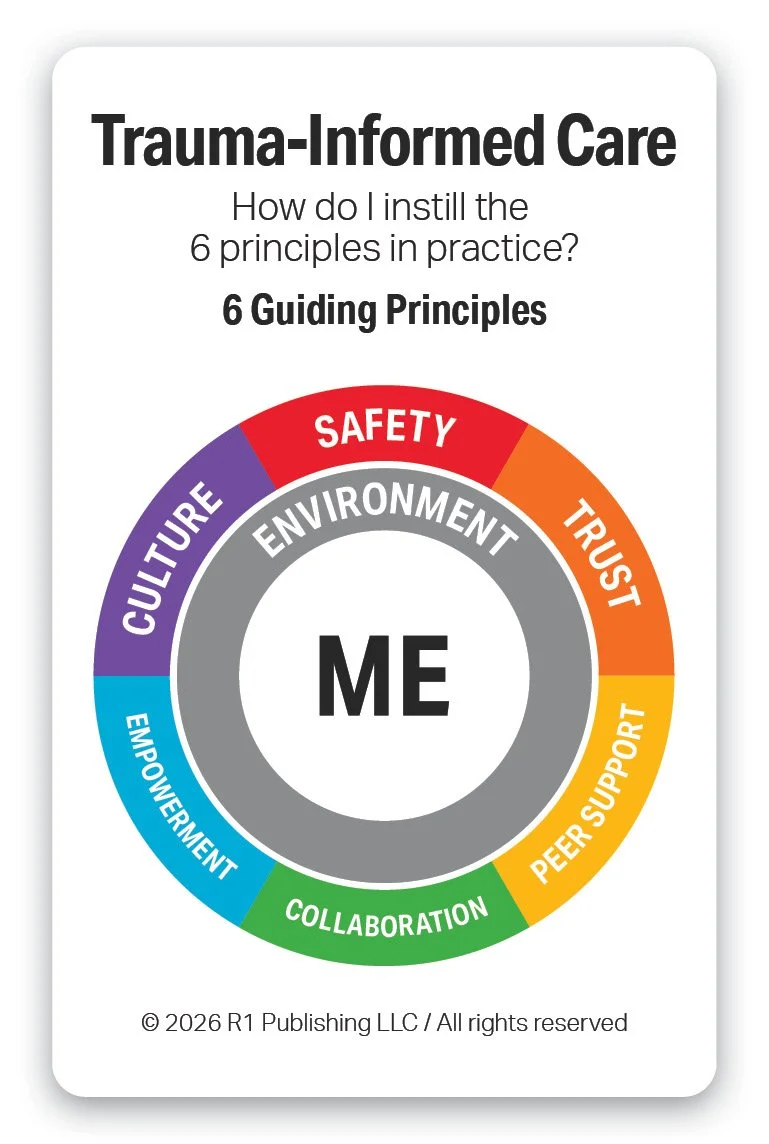

Trauma-Informed Care (TIC) is an evidence-based practice that recognizes the widespread impact of trauma and integrates this understanding into all aspects of service delivery. It emphasizes safety, trustworthiness, peer support, collaboration, and empowerment to avoid re-traumatization. Rather than focusing on “what’s wrong,” it asks “what happened” and responds with sensitivity to lived experiences. The purpose of Trauma-Informed Care is to promote engagement and healing by creating supportive environments that foster resilience and recovery.

R1 enhances TIC by providing a concrete set of tools for learning about and assessing oneself on key behaviors linked to the 6 guiding principles of Trauma-Informed Care. R1 offers tools for both Trauma-Informed Care (ME) for staff and Trauma-Informed Care (WE) for clinical and peer supervision.

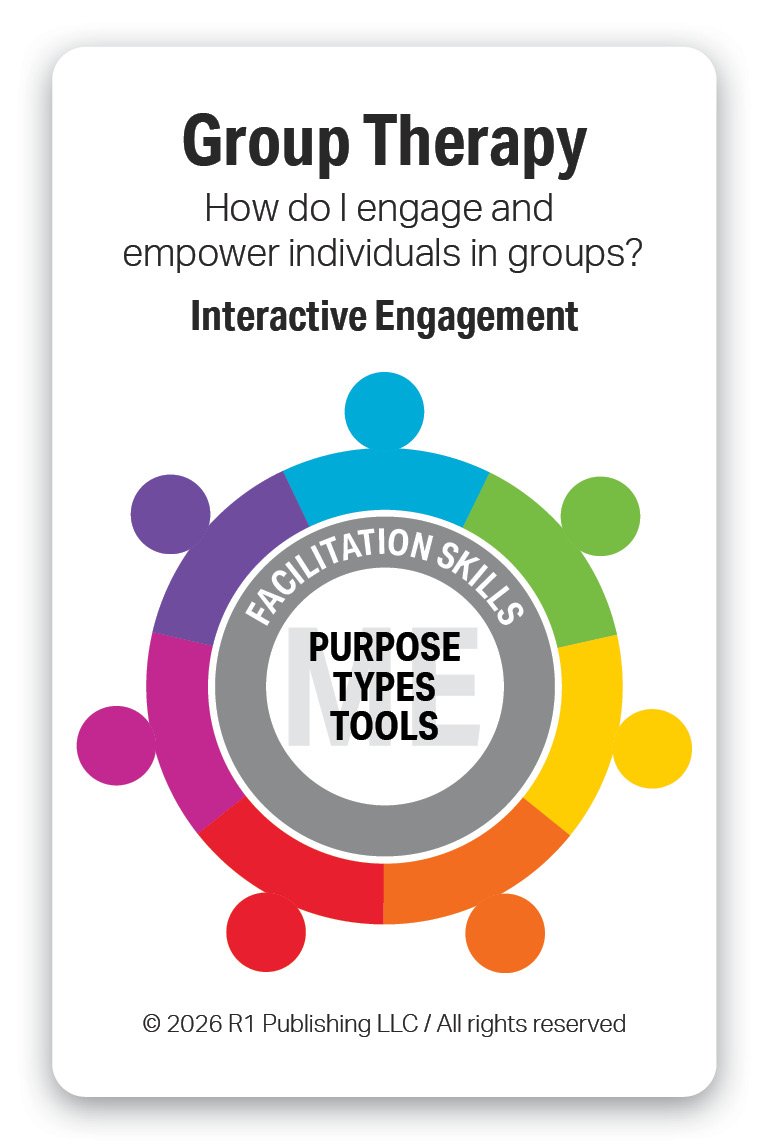

Group Therapy is an evidence-based practice in which individuals work together with a trained facilitator to address shared challenges and goals. It provides opportunities for peer support, skill-building, and learning through shared experiences and feedback. Participants benefit from increased connection, accountability, and normalization of their experiences. The purpose of Group Therapy is to promote personal growth and behavior change while reducing isolation and strengthening interpersonal skills.

R1 enhances Group Therapy by providing an interactive, comprehensive, modular, topical, plug-and-play set of Group Kits for group engagement and education. All of the evidence-based topics in the R1 Learning System are packaged in Group Kits for in-person settings. All of the R1 topic tools are also available on the R1 Discover App for use virtual groups. Each Group Kit provides multiple activities for use pre-setting, in-setting, and post-setting. Group Kits are available in Group Kit Bundles ranging from 6-24 Group Kits per Bundle.

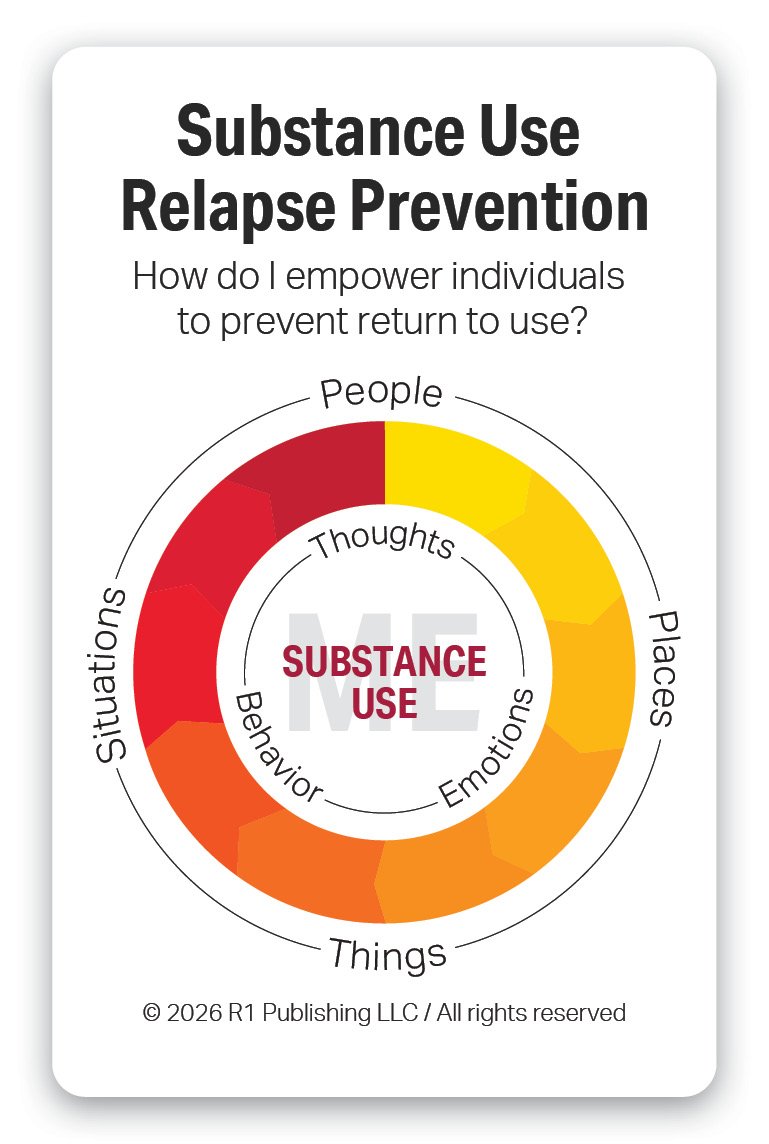

Substance Use Relapse Prevention is an evidence-based practice focused on helping individuals maintain recovery by anticipating and managing situations that increase the risk of returning to substance use. It teaches skills to recognize triggers and warning signs, cope with cravings, and respond effectively to high-risk situations. Substance use prevention emphasizes self-awareness, planning, and building healthy alternatives to harmful use. Its purpose is to support long-term recovery by reducing substance use risk and strengthening confidence in maintaining sobriety.

R1 enhances Relapse Prevention by providing both hands-on and online tools for core topics such as Stages of Change for Substance Use, Substance Use, Substance Use Triggers, Substance Use Warning Signs, and Recovery Capital. Additional behavioral health topics are available for to support Co-occurring Disorders and Trauma-Informed Care settings.

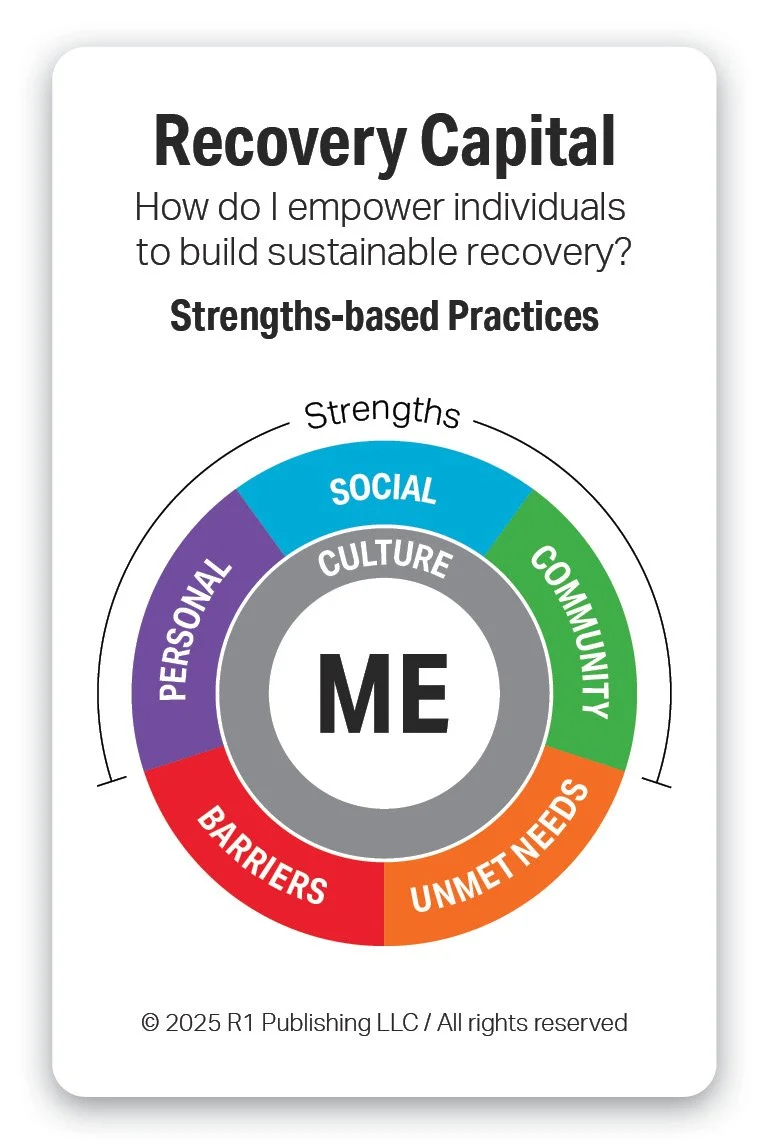

Recovery Capital is an evidence-based framework that refers to the internal and external resources individuals can build and draw upon to sustain recovery from substance use and mental health challenges. It includes personal strengths, social supports, community resources, and cultural and environmental factors. As a practice, it focuses on identifying, building, and leveraging these assets over time. The purpose of Recovery Capital is to strengthen long-term recovery by increasing access to supports that promote stability, resilience, and overall well-being. These strengths can be used to effectively address barriers and unmet needs.

R1 enhances Recovery Capital by providing assessments, tools, and training for successfully implementing recovery capital with a wide range of populations in a variety of settings. Our Recovery Capital Screener (RCS-36) provides the measurement and directional framework for structured engagement. Our Recover Capital tools provide a strength-based approach for engagement, education, and goal setting. All of the topics in the R1 Learning System and on the R1 Store are mapped to the Recovery Capital model and provide a wealth of videos and activities for on-going exploration and impact.

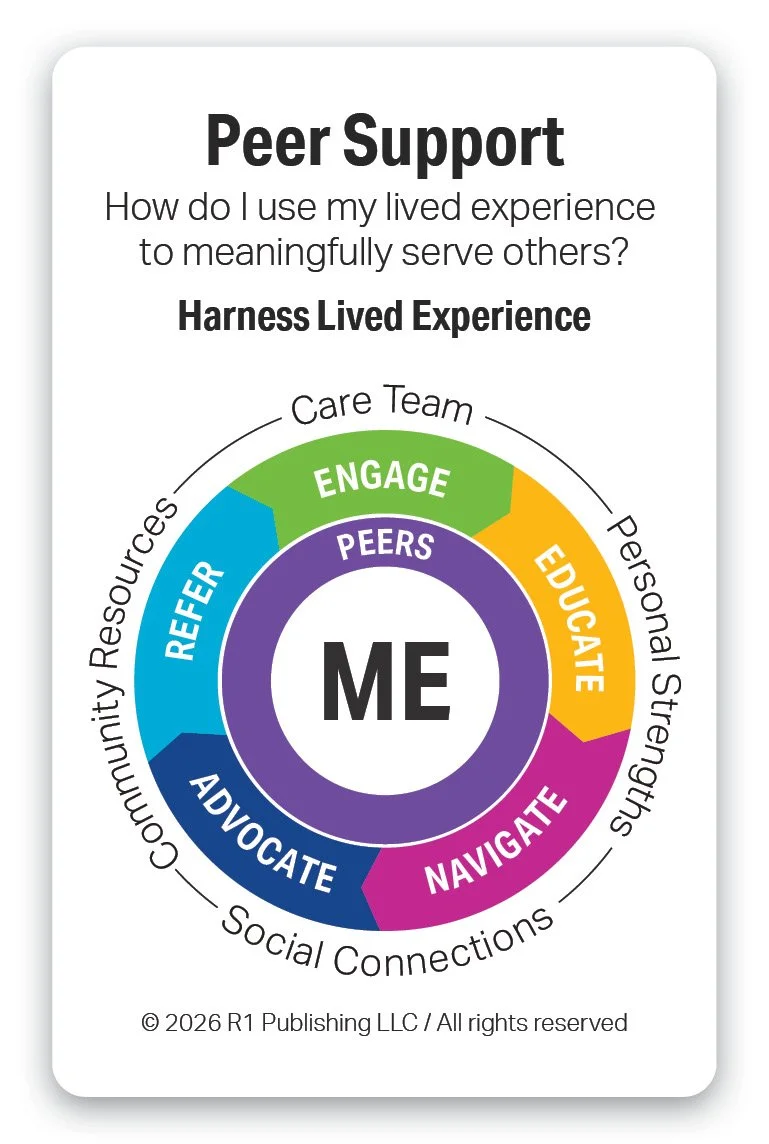

Peer Support is an evidence-based practice in which individuals with lived experience of recovery provide support, guidance, and encouragement to others facing similar challenges. It is grounded in mutuality, shared understanding, and hope rather than clinical authority. Peer Support helps individuals build confidence, navigate systems of care, and develop coping and self-advocacy skills. Its purpose is to enhance engagement, empowerment, and long-term recovery by fostering connection and shared resilience.

R1 enhances Peer Support by providing concrete interactive educational and skill building tools for peer support training and certification programs. The R1 Discover App provides on-the-job training and development tools for all of the topics in the R1 Learning System. R1 Discover tracks and reports on utilization, engagement, and impact. All of the hands-on Discovery Cards and Group Kits support in-person engagement and education as peers navigate, advocate, and refer individuals to social connections and community resources.

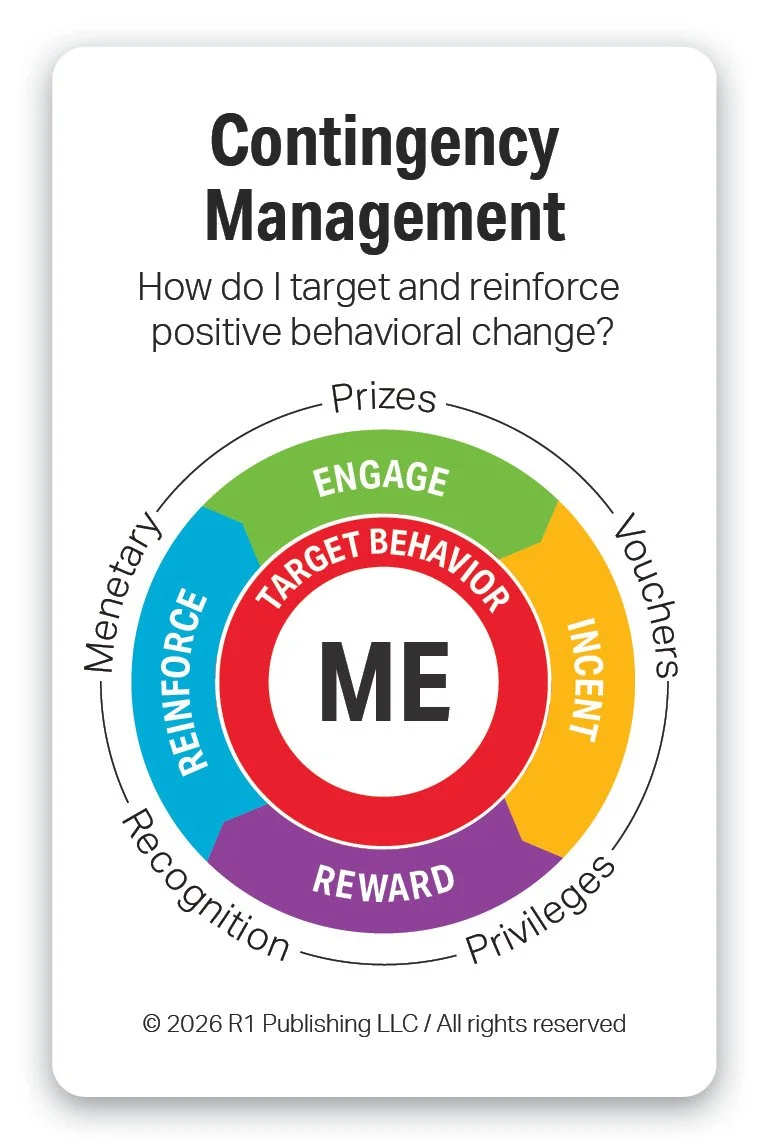

Contingency Management is an evidence-based behavioral health practice that uses positive reinforcement to encourage healthy behaviors, such as treatment attendance or abstinence from substances. Individuals receive tangible rewards or incentives when they meet clearly defined goals. This approach is grounded in behavioral science and has strong evidence for effectiveness, particularly in substance use treatment. Its purpose is to increase motivation, reinforce positive behavior change, and support sustained recovery.

R1 enhances Contingency Management by providing on-line evidence-based educational videos, interactive activities, and resources for core topics in behavioral health, substance use & addiction, and life & work skills. Through R1 Discover’s application programing interface (API) services, R1 Discover can be quickly added to the libraries of third-party apps, case management systems, and electronic medical record systems to be used as additional interactive resources for contingency management.

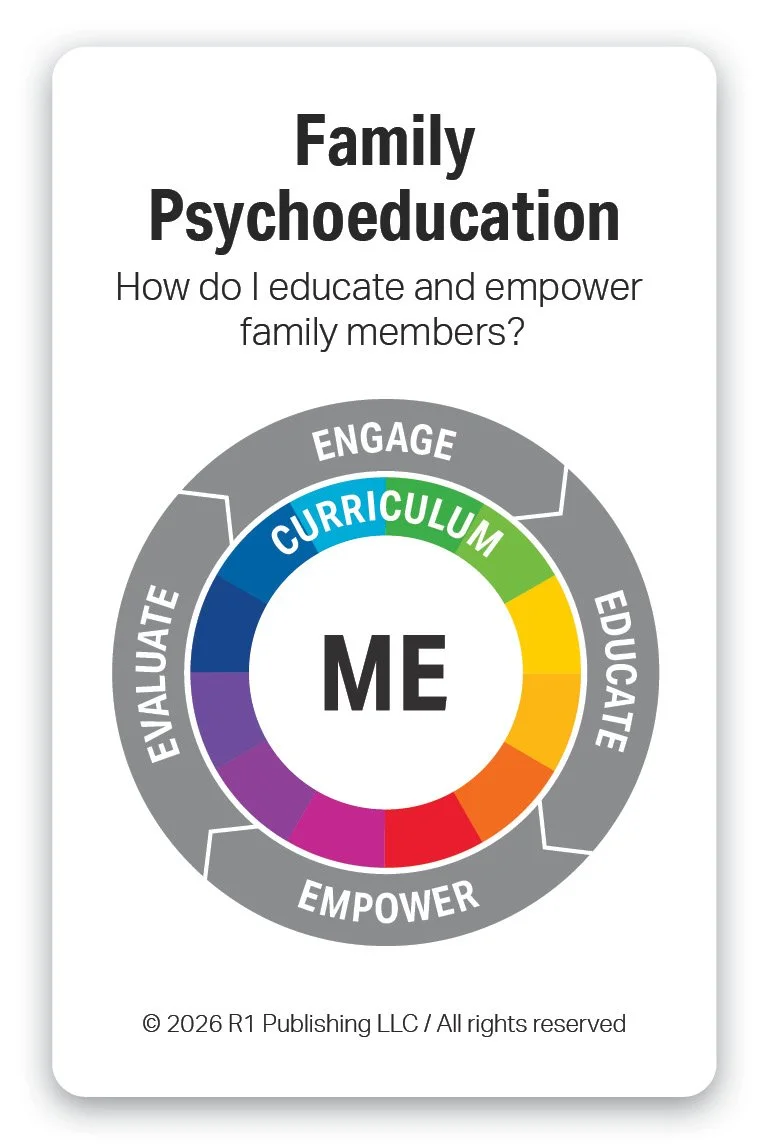

Family Psychoeducation is an evidence-based practice in behavioral health that involves educating family members about mental health and substance use conditions, treatment approaches, and recovery strategies. It helps families develop effective communication, problem-solving, and coping skills. By increasing understanding and reducing stigma or blame, family psychoeducation strengthens family support for the individual in treatment. Its purpose is to improve outcomes by enhancing family involvement, stability, and long-term recovery.

R1 enhances Family Psychoeducation by providing evidence-based videos, interactive activities, and curriculum resources for topics in mental health & wellness, substance use & addition, and life & work skills. The comprehensive, modular, plug-and-play topical tools can supplement existing family programs or be built into a new customized one. Both the hands-on tools and online R1 Discover App can be used to increase engagement, learning, and impact in both group and 1-on-1 settings.

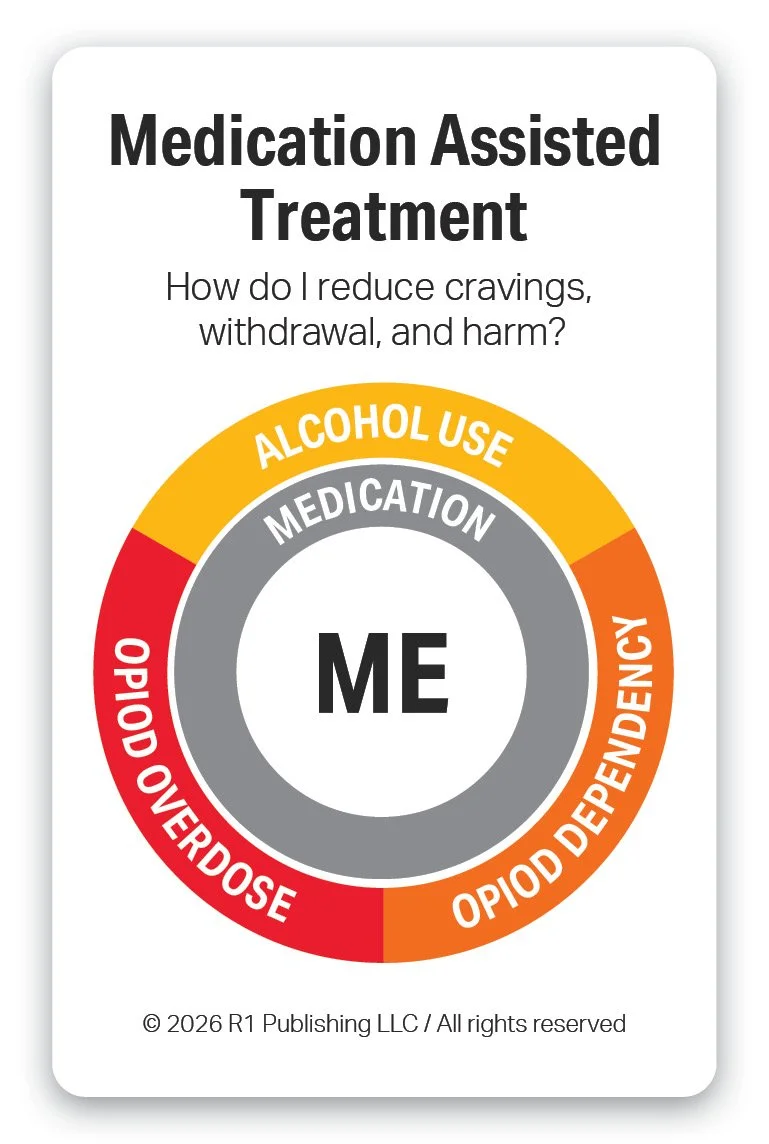

Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) is an evidence-based practice that combines FDA-approved medications with counseling and behavioral therapies to treat substance use disorders. Medications help reduce cravings, manage withdrawal symptoms, and stabilize brain chemistry. When integrated with therapeutic support, MAT improves treatment retention and reduces the risk of relapse and overdose. Its purpose is to support recovery and improve overall functioning by addressing both the biological and behavioral aspects of addiction.

R1 enhances MAT by increasing staff development and retention… and providing interactive educational tools to increase engagement for individuals in 1-on-1s and groups. How do programs get individuals to counseling that don’t want counseling? How do programs increase attendance for groups? The R1 hands-on tools increase engagement, learning, and connection in groups. R1 Discover provides online tools that increase engagement when used for pre-work, post-work, and interactive activities during in-person virtual sessions. R1 support Opioid Treatment Programs (OTPs) nationally.

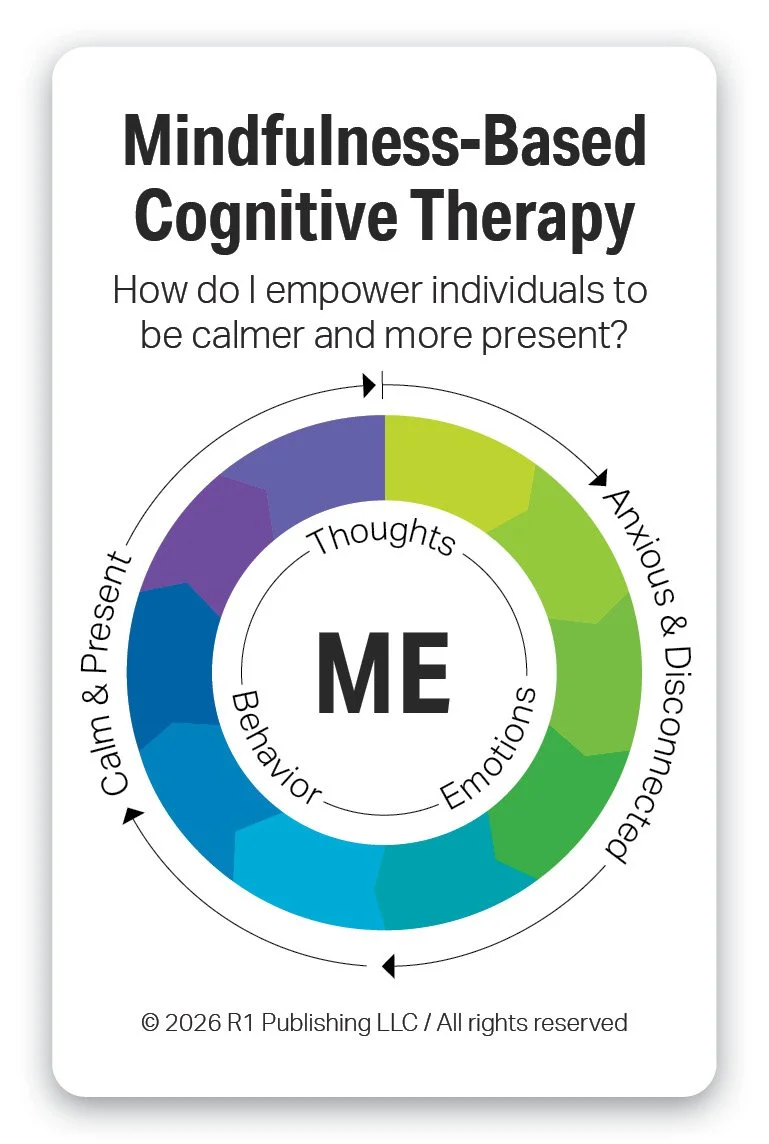

Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) is an evidence-based psychotherapy that integrates cognitive therapy principles with mindfulness practices. It helps individuals become more aware of their thoughts and emotions and relate to them with curiosity rather than judgment. By interrupting automatic negative thinking patterns, MBCT reduces the risk of relapse, particularly for depression. Its purpose is to support emotional regulation and long-term mental health by cultivating present-moment awareness and self-compassion.

R1 enhances MBCT by providing interactive, reflective, and expressive tools for emotional regulation and resilience practices. R1’s roadmap for 2026 includes topics for Mindfulness Practices, Emotional Regulation Practices, Resilience Practices, and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. These topics will each include ideas and strategies to help individuals be calmer and more present.

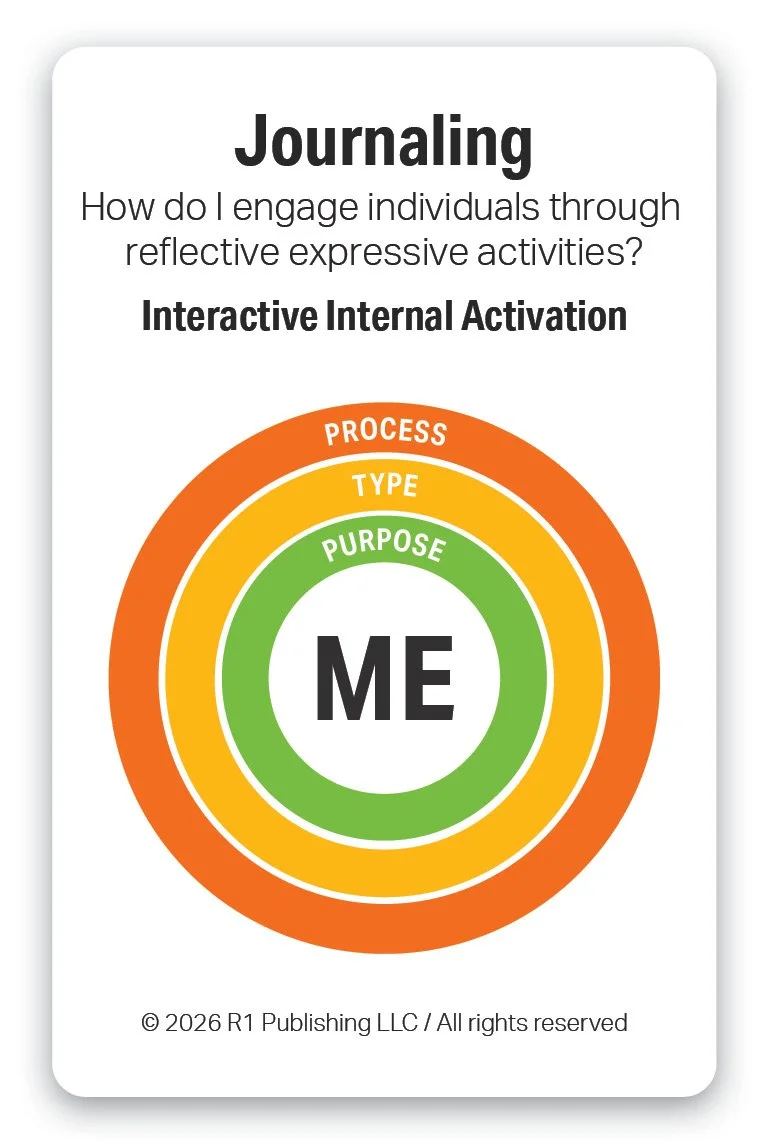

Journaling is an evidence-informed behavioral health practice that involves regularly writing about thoughts, emotions, and experiences to promote self-reflection and emotional processing. It helps individuals increase awareness of patterns, triggers, and progress over time. Research shows journaling can reduce stress, improve mood, and support coping skills when used consistently. Its purpose is to enhance emotional regulation, insight, and overall mental well-being.

R1 enhances Journaling by increasing and enhancing the vocabulary of individuals for effective journaling. Each of the R1 topics provides a wealth of interactive activities for individuals to self-reflect, build vocabulary, and learn to express themselves in both group and 1-on-1 settings. The Discovery Cards, both hands-on and online, build vocabulary, increase literacy, and provide the foundation for effective journaling. Every Discovery Card can be used as a focused prompt for journaling – values, character traits, emotions & feelings, affirmations, and more. Link to Journaling Worksheet.

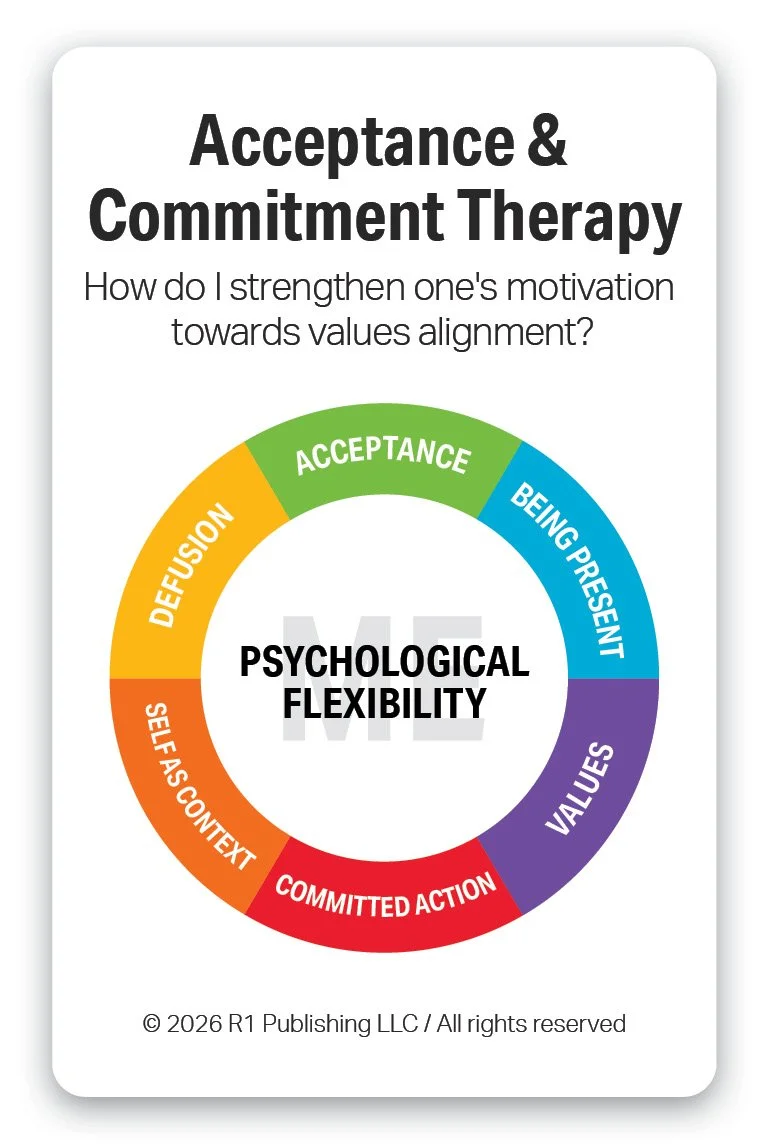

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is an evidence-based practice that helps individuals develop psychological flexibility by accepting difficult thoughts and emotions rather than trying to avoid or control them. It emphasizes mindfulness, values clarification, and committed action toward meaningful life goals. ACT teaches people to observe their experiences with openness while choosing behaviors aligned with their values. Its purpose is to reduce distress and improve well-being by helping individuals live more fully and purposefully, even in the presence of challenges.

R1 enhances ACT by providing tools for individual and group engagement specific to Values and wellness topics. R1’s Values topic, based on the Swartz Values Wheel, provides a culturally sound foundation for identifying values from which to evaluate one’s commitment to action based on values alignment. R1’s wellness topics such as Recovery Capital and 8 Dimensions of Wellness (Coming 2026), provide a wealth of positive strength-based behaviors for individual to use for setting SMART Goals.

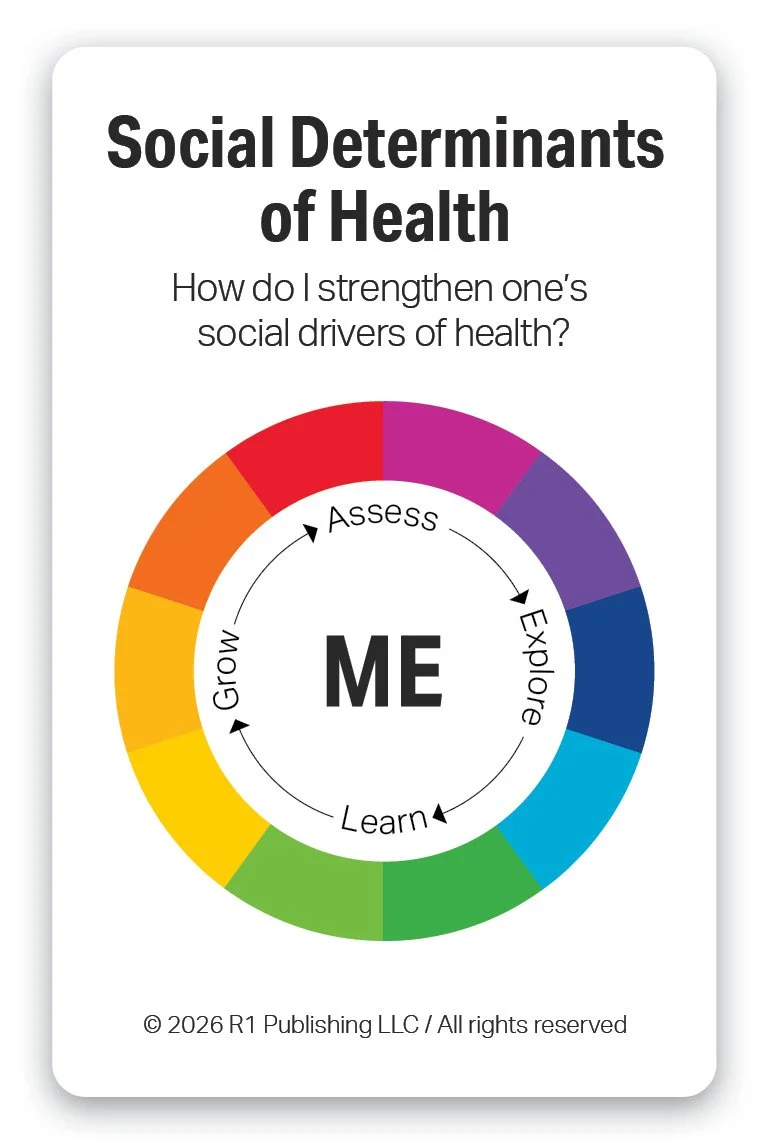

Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) are the evidence-based conditions and social factors in the environments where people live, learn, work, and age that strongly influence health outcomes. As an evidence-based practice, addressing SDOH focuses on identifying and reducing barriers such as housing, food access, transportation, education, and income to improve health and equity. Its purpose is to reduce health disparities and strengthen overall well-being by targeting the root social and structural drivers of health.

R1 enhances SDOH by educating practitioners and individuals on their importance for health outcomes. R1 currently connects the Social Determinants of Health to R1’s wellness topics such as Recovery Capital and 8 Dimensions of Wellness (Coming 2026). These topics provide a wealth of positive strength-based behaviors for individual to use for setting SMART Goals.

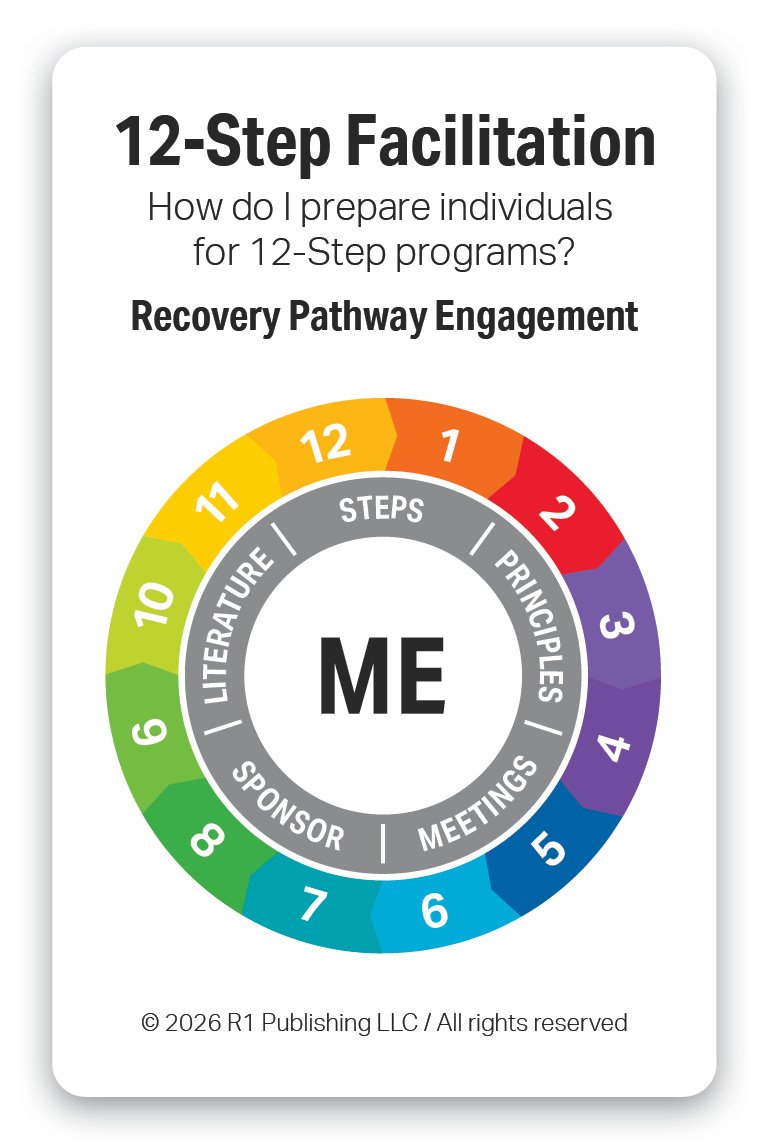

12-Step Facilitation is an evidence-based practice designed to encourage engagement in 12-Step mutual support programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Narcotics Anonymous (NA). It helps individuals understand the principles of the 12-Step model and build motivation to participate in peer-led recovery communities. The approach emphasizes acceptance, surrender, and active involvement in recovery-supportive activities. Its purpose is to promote sustained recovery by strengthening social support and ongoing engagement in abstinence-oriented programs.

R1 enhances 12-Step Facilitation by providing vocabulary building tools for recovery pathways such as 12-Step, SMART Recovery, Celebrate Recovery and others. The Consequences of High-Risk Behaviors can be used for Step 1 to help individuals identify the impact, cost, loss, and harm of their patterns of behavior. Character Traits provides examples for strengthening in Steps 6 and Step 7. Recovery Capital highlights the importance on build Community Capital, strength-based capital for recovery community participation and social relationships.

References

Sackett, D. L., Rosenberg, W. M. C., Gray, J. A. M., Haynes, R. B., & Richardson, W. S. (1996). Evidence based medicine: What it is and what it isn’t. BMJ, 312(7023), 71–72. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71

Sackett, D. L., Straus, S. E., Richardson, W. S., Rosenberg, W., & Haynes, R. B. (2000). Evidence-based medicine: How to practice and teach EBM (2nd ed.). Churchill Livingstone.

Guyatt, G., et al. (Eds.). (2015). Users' guides to the medical literature: A manual for evidence-based clinical practice (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

Straus, S. E., Glasziou, P., Richardson, W. S., & Haynes, R. B. (2019). Evidence-based medicine: How to practice and teach EBM (5th ed.). Elsevier.

Melnyk, B. M., & Fineout-Overholt, E. (2019). Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: A guide to best practice (4th ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

Melnyk, B. M., & Fineout-Overholt, E. (2022). Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: A guide to best practice (5th ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

LoBiondo-Wood, G., & Haber, J. (2022). Nursing research: Methods and critical appraisal for evidence-based practice (10th ed.). Mosby.

Higgins, J. P. T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M. J., & Welch, V. A. (Eds.). (2022). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119536604

Cochrane Library. (n.d.). Cochrane database of systematic reviews. Wiley Online Library