How Do I Build the Skills for Change? The R1 Learning Process

“Engagement” has been at the heart of R1’s mission from the very start. Our focus has been on engaging individuals, practitioners, and organizations with the leading evidence-based strategies for substance use disorder and mental health and wellness.

“Engagement” is a broad term that can mean many and varied things. From our perspective, we think of engagement on multiple levels.

For individuals, it means we seek to make them active participants in learning the skills to direct their own recovery.

For practitioners, it means providing all the tools, training, and support necessary to adopt evidence-based strategies into practice.

For organizations, it means offering a common process and structure for implementation of and ongoing fidelity to a comprehensive catalog of evidence-based strategies.

We arrived at our formulation of the R1 Learning Process from the reading and research we do into how to create maximum engagement with learning and behavioral change. Specifically, we were inspired by a small but vital component of Albert Bandura’s work in learning theory and behavioral change. When discussing his theory of Self-Regulation, Bandura established a shorthand framework for the cognitive process that individuals use as they learn or adapt information into behaviors.

“[H]uman behavior is extensively motivated and regulated by the ongoing exercise of self-influence. The major self-regulative mechanism operates through three principal subfunctions. These include self-monitoring of one’s behavior, its determinants, and its effects; judgment of one’s behavior in relation to personal standards and environmental circumstances; and affective self-reaction.” (Bandura 1991)

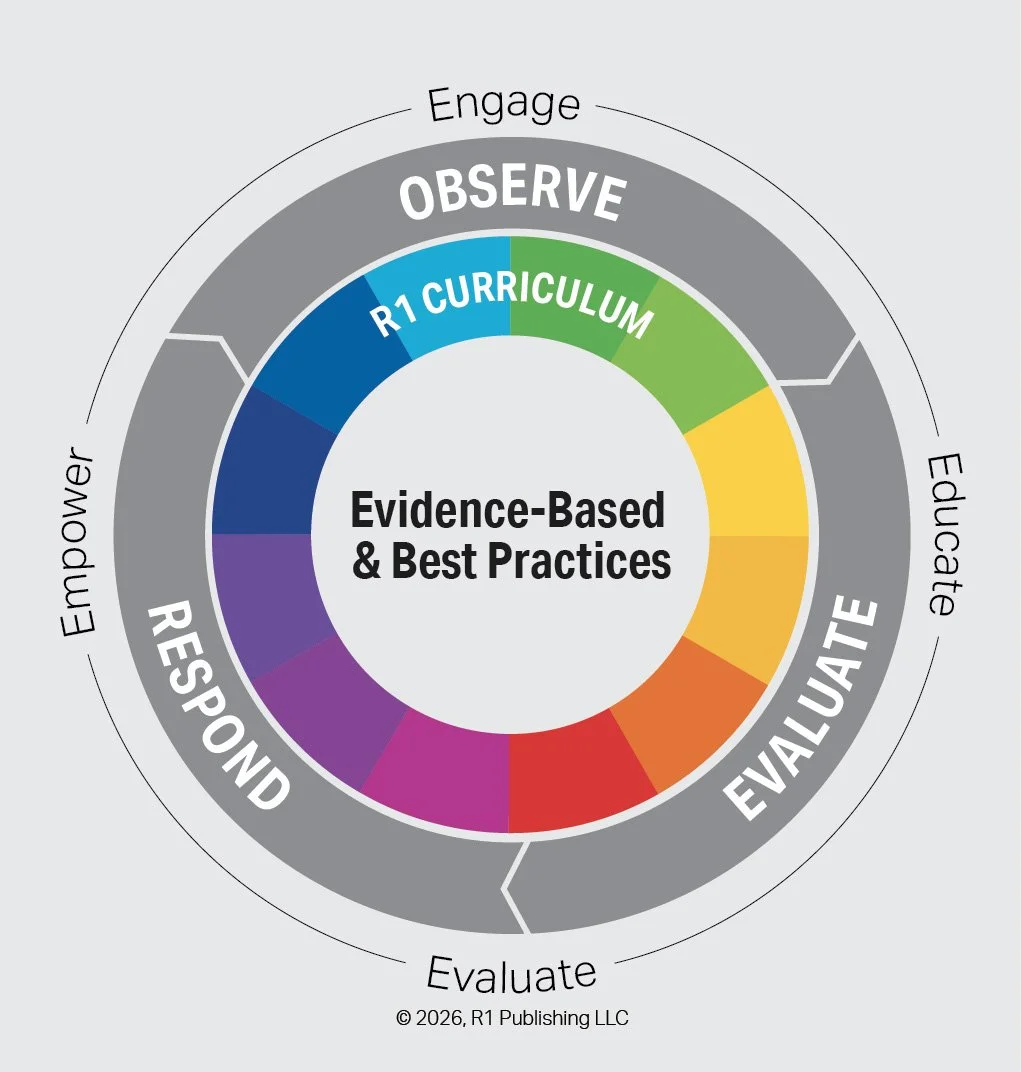

Bandura was not alone in describing an individual’s cognitive process in this structure. His original theory has since been expanded upon and incorporated into larger learning and behavioral theories such as Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) and Social Learning Theory (SLT), but the self-regulative element remains within them. Depending on the writer and the specific writing, different terms may be used, but descriptions of the self-regulative process almost always center on the interaction of three core elements: Observe, Evaluate, Respond.

From Self-Regulation to Self-Efficacy

“Person-Centered” and “Strengths-Based” have become buzzwords (kind of like “Evidence-Based”). Despite any overuse or misuse, they became popular because they had fundamentally strong underpinnings. “Person-Centered” strategies are designed to be less proscriptive and prescriptive so the individual has room to take on more of the lead role in their own recovery. “Strengths-Based” approaches seek to leverage skills, resources, and abilities that people already possess and deploy them toward recovery and empowerment.

Part of what makes the Observe, Evaluate, Respond process so effective is that there is nothing new about it. It merely strengthens innate skills through practice while directing those skills toward desired actions. Moreover, the practice reinforces itself and builds self-efficacy and motivation along the way. Self-efficacy was also originally conceived by Albert Bandura. It refers to one’s belief in one’s own resources and abilities to overcome prospective challenges. Greater self-efficacy builds greater motivation and culminates in the confidence that one can self-direct their long-term recovery.

We all observe, evaluate, and respond many times each day by instinct. As we developed the R1 Learning Process we tried noticing how we use it in our normal daily routines. Each morning, I open the refrigerator and observe the contents. I evaluate what breakfast I can create from the available ingredients, and I respond by designing a plan of action for making oatmeal, yogurt and berries, leftover pizza, etc… Over breakfast I will observe my schedule for the day and check emails. I evaluate what I need to get done today and I respond by planning my actions for the day. The more I did it, the more I noticed the practice shifted my responses. I grabbed the leftover pizza less and the heartier oatmeal and yogurt more often.

Building the Skills for Change

There wasn’t a light bulb moment when we first ran across this process. But the more research we did on engagement and the more evidence-based strategies we adapted into structured Discovery Cards modules, the more we started to notice that the process of Observe, Evaluate, Respond was everywhere. For example, when working on our new Defense Mechanisms module we found George Vaillant’s thoughts on the two primary types of effective coping strategies:

“One form of coping involves eliciting help from appropriate others, for example, by mobilizing social support. A second form of coping includes voluntary cognitive efforts, such as information gathering [Observe], anticipating danger [Evaluate], and rehearsing responses to danger [Respond].” (Vaillant 1994) [Emphasis added]

The R1 Learning Process isn’t just for the individual. It works equally well as a framework for practitioners to instill these skills. Motivational Interviewing (MI) is a common and effective counseling approach. Part of the MI technique is “reflective listening”, a process of observing an individual for change language and motivation; evaluating progress toward desired change or goal, and responding by higlighting the individual’s strengths, reiterating or repackaging statements, and refocusing on goals if necessary.

The R1 Learning Process serves our engagement goals perfectly.

For individuals, the practice builds their skills for change and allows them to self-direct their own long-term recovery.

For practitioners, the practice provides an approachable and repeatable structure into which engaging evidence-based and best practice treatment strategies can be plugged and played.

For organizations, the process generates efficiencies in the implementation and use of evidence-based strategies.

For all involved, the process produces standardized and comparable outcome metrics.

The R1 Learning Process in Practice

Implementation is often the barrier to success when adopting evidence-based practices into a program. The R1 Learning System is designed to equip practitioners at all levels of knowledge, skill, and experience with the tools and support needed to effectively adopt and use evidence-based strategies. The Discovery Cards provide a modular approach for adopting an approachable and repeatable learning experience for individuals in treatment and recovery.

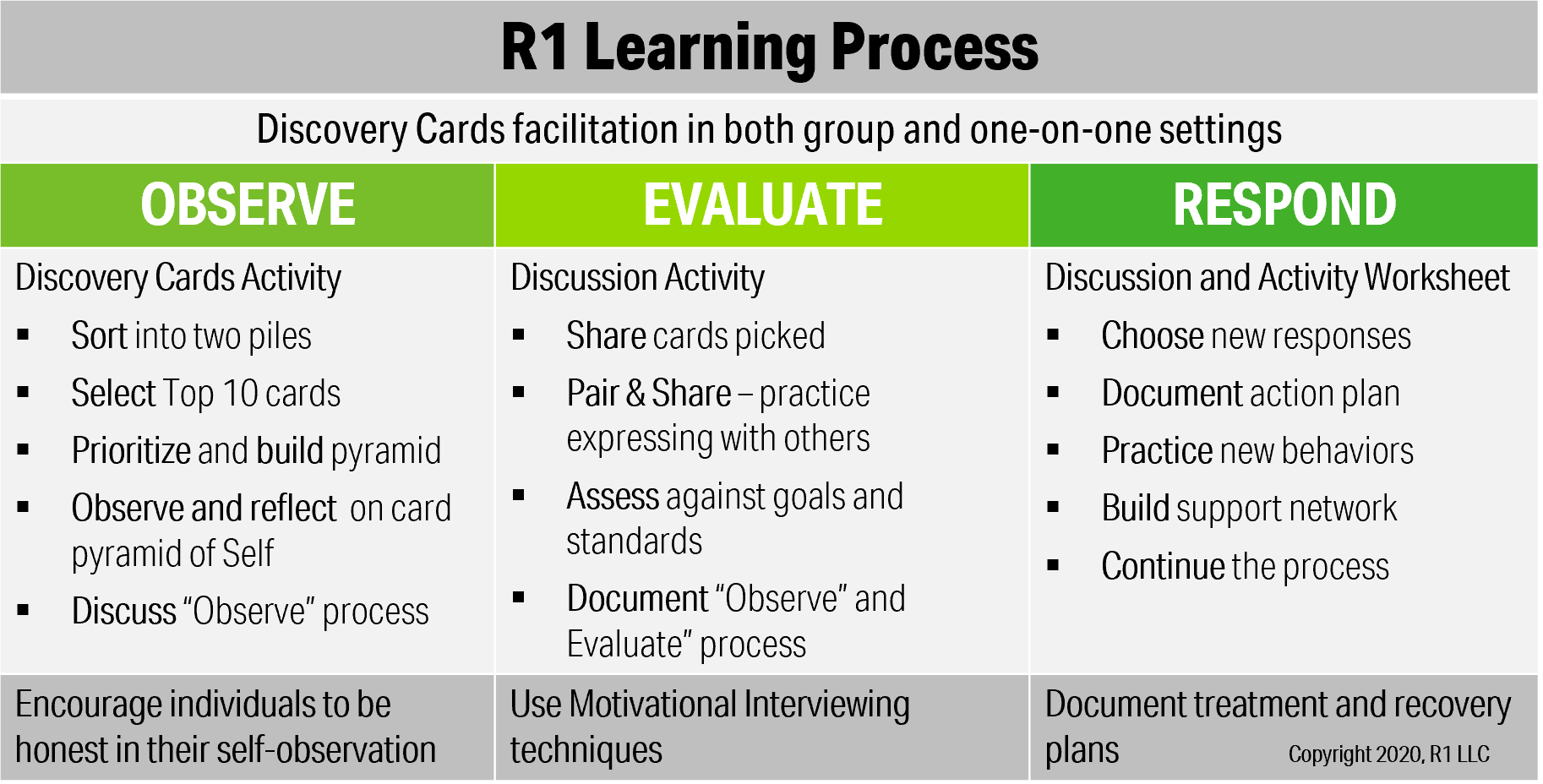

The table below highlights how we use the R1 Learning Process in practice. Each group or one-on-one session is designed to include situational exercises that cultivate this skill-building practice. Describing the process during the sessions is vital, so that people see the relationship between the activity and the skills they are honing. The subject matter, context, and specific objectives of the Observe, Evaluate, Respond practice vary by activity and topic, but the overarching process for developing the practice remains consistent.

Discovery Card activities were designed around the Observe, Evaluate, and Respond framework. The process is used multiple times at multiple levels within the activity. The typical Discovery Cards structure includes the following components:

Learning Objectives - Goals against which individuals observe, evaluate, and respond.

“Step” Level - Each activity is comprised of multiple steps, each using the process to generate insights.

“Activity” Level - Activities include steps for observing, evaluating, and responding to the cumulative step insights.

“Module” Level - Discovery Card modules (topics) include multiple activities.

By inserting the process at multiple levels in each module, individuals gain understanding and competence in applying it to themselves and their behavior, increasing their motivation to move forward and their confidence in their abilities to do so. Moreover, the process works in an iterative fashion. Activities guide individuals to use the process around specific items first, then use it again as those specific items are rolled up into larger insights. For example, within the Relapse Triggers module,

Individuals first Observe, Evaluate, and Respond to external (environmental) cues that spark thoughts or cravings toward active use or other unhealthy behaviors.

Next, individuals Observe, Evaluate, and Respond to the internal (emotional) triggers that were elicited by that external (environmental) trigger.

Finally, individuals observe the full profile of their triggers; including both external and internal triggers, as well as the interplay between the two. Individuals typically observe that their personal triggers are focused in certain areas. This allows them to focus their evaluation on the areas of most concern, and respond by creating plans of action that directly address those areas.

The end result is that individuals learn that Relapse Triggers are not one-dimensional, that there is an interplay between external and internal triggers, and that a common process of self-observation, self-evaluation, and self-response can be applied to gain actionable insights and to create personal action plans based on those insights.

The R1 Learning Process in Action

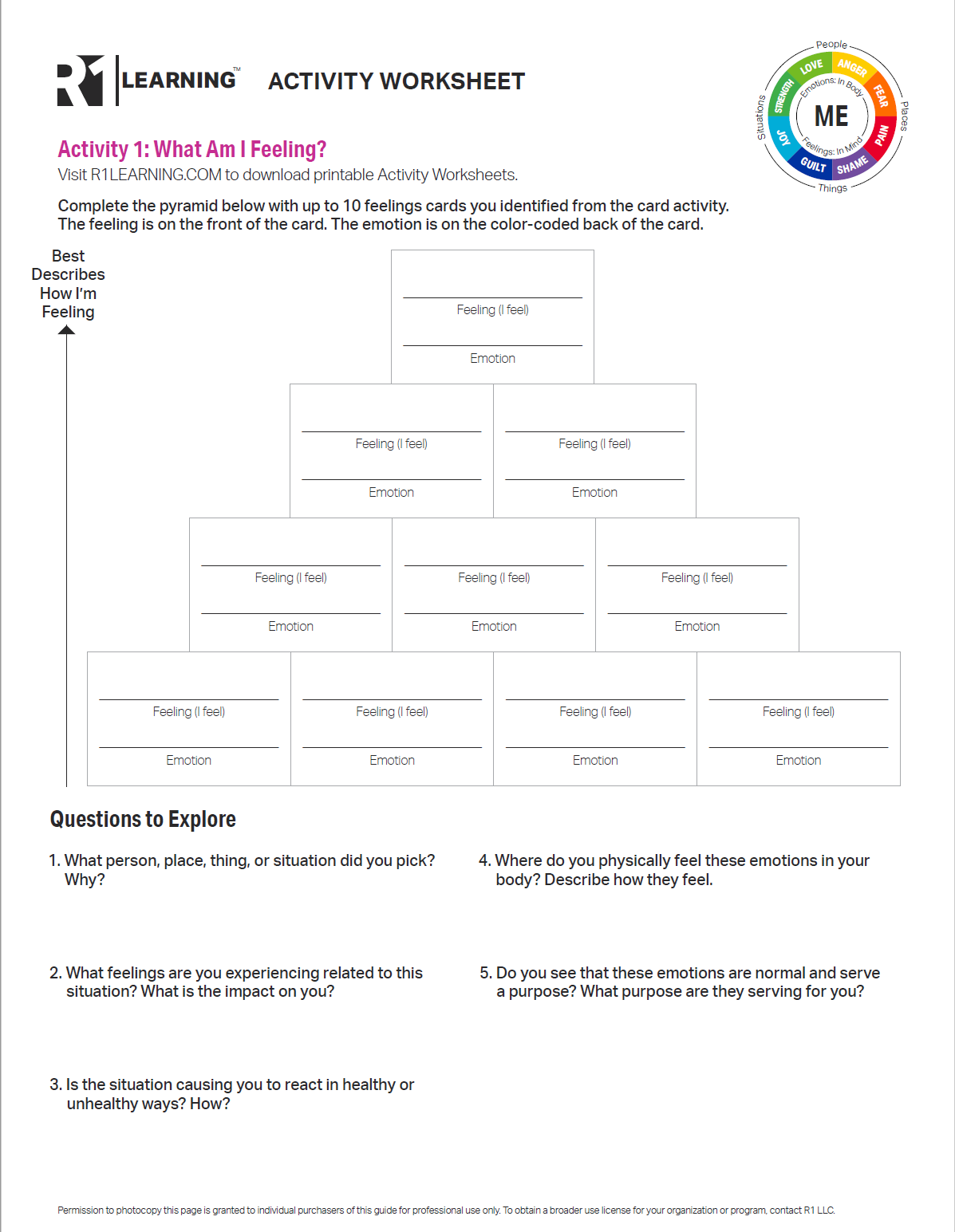

Below we use the R1 Discovery Cards Emotions & Feelings module to go a little deeper into how the R1 Learning Process works at multiple levels to cultivate the Observe, Evaluate, and Respond practice.

The example below highlights how we apply the R1 Learning Process to specific R1 topics. Each of the activities and group exercises in the Discovery Card modules have been designed to explicitly illustrate the Observe, Evaluate, Respond portions.

Observe: The first activity in the Discovery Cards Emotions & Feelings module asks individuals, “What am I feeling?” as they look at a current or past environmental trigger that activates an emotional response in them. In this activity, individuals work through a 3-step card-sorting activity that leads to a “summary” card pyramid of their emotions and feelings around this trigger. Individuals start by observing the 40 Feelings sorting cards, looking for the cards that reflect something specific they are feeling around that emotional cue. This activity helps individuals to start consciously and purposefully practicing the skill of self-observation. The Discovery Cards also provide both a vocabulary and a taxonomy so both individuals and practitioners are speaking in common terms. Additionally, the color-coded sorting cards for the 8 Core Emotions enable individuals to observe common aspects of what they are experiencing.

The interaction of the three components is at work within the Observe step of the activity. After observing the sorting cards, individuals first evaluate whether the card shows a feeling they are feeling or not, and then respond by placing the card in pile #1 or pile #2.

Evaluate: The card pyramid takes the individual feelings that were selected and reveals the top emotions. This summary shows individuals which emotions are being triggered. The evaluation step occurs as individuals look at these results, assess and share about the cards they picked, what resonated with them, what surprised them, etc… The evaluation process helps to illustrate common themes and highlight the triggers that are most important to address.

Respond: The Discovery Cards enable individuals to select emotional regulation practices and specific coping skills to support new responses. In this example, individuals are provided with a set of ten emotional regulation practice cards (grey cards) with a list of specific coping skills on the card backs. The cards offer individuals the opportunity to choose from several regulation strategies. When joined with the insights gained from the Evaluation step, individuals can focus on areas to practice and build support from others. Activity Worksheets are provided to document responses for future reference or inclusion in treatment or recovery plans.

Just as in the Observe step, the Evaluation and Respond steps also have the process at work within the step. Individuals observe the Emotional Regulation strategies and evaluate their applicability to the areas of concern and respond by selecting that strategy (card) or discarding it.

The examples above illustrate just one aspect of the R1 Learning Process at work within one activity of one topic. The structure is at work comprehensively across each activity, topic, and curriculum. This pervasive interplay of the process helps to strengthen the practice and provide individuals with the self-efficacy to see, understand, and address the challenges they face. Repetition reinforces that confidence, increases motivation and application of the process, and builds the skills for change. .

References

Bandura, Albert. (1991). Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, 50(2), 248-287.

Baumeister, R. F., & Heatherton, T. F. (1996). Self-regulation failure: An overview. Psychological inquiry, 7(1), 1-15.

Schunk, D. H. (1994). Self-regulation of self-efficacy and attributions in academic settings.

Schunk, D. H., & Zimmerman, B. J. (Eds.). (2012). Motivation and self-regulated learning: Theory, research, and applications. Routledge.

Vaillant, G. E. (1994). Ego mechanisms of defense and personality psychopathology. Journal of abnormal psychology, 103(1), 44.

Copyright 2023 R1 Publishing LLC / All Rights Reserved. Use of this article for any purpose is prohibited without permission.