The 5 Stages of Change and the Transtheoretical Model (TTM) — Do I Know the Basics?

Teaching others to learn and apply the fundamentals of behavioral health evidence-based theories and best practices is why R1 Learning exists. Our mission is to curate the most impactful work from experts in the field and put them into the hands of practitioners (clinicians, counselors, coaches, peer support providers, and educators) at all levels of knowledge, skills, and experience, and increase their effectiveness. Our goal is also to put these same theories and tools into the hands of individuals in treatment and recovery so that they can understand them more quickly and concretely, and empower them to change toward healthier behavior. Stages of Change was the first topic we identified for the R1 Learning System. It was our first Discovery Cards Deck and Group Kit thanks to the gracious support and review by Drs. Prochaska (James and Janice) and DiClemente (Carlo). It is a fundamental body of knowledge and one that we think will stand the test of time for decades to come. Our goal for today’s post is that you will walk away with the fundamentals of the Stages of Change and be able to apply it in your next one-on-one or group session. Let’s start with the basics… what is change?

Change — the act or process of transforming, shifting, or becoming different in nature

Change is one of the most difficult behavioral processes. Why and how do people change? What is the role of motivation in the change process? Extensive research has been conducted to answer such questions.

The Change Process. Research has noted that change is a process. Change is rarely a single moment in time. It occurs

over time. It has stages and processes. To better understand and illustrate how change occurs, researchers often develop

models and theories. A pair of researchers — Drs. James Prochaska and Carlo DiClemente — closely examined theories about how people change. They also developed a model based on the body of work they studied. Because their model emerged from reviewing multiple psychological and behavioral theories about how change occurs, they described their biopsychosocial framework for understanding addiction as “transtheoretical.” Their Transtheoretical Model (TTM) of Change explains that the change process is a sequence of stages through which people progress as they consider, start, and maintain new behaviors. Drs. Prochaska and DiClemente refer to the Stages of Change Model as a way of illustrating the change process, understanding what stage individuals are progressing through, and identifying strategies that enhance individuals’ motivation to progress to the next stage.

Explore R1 Discover — Interactive Engagement Tools

The Transtheoretical Model — Drs. Prochaska & DiClemente

The TTM, and particularly the Stages of Change Model, is one of the leading models in behavioral health and has been applied to many different behavioral health issues beyond its original focus in smoking cessation. Because of the TTM’s focus on the behavioral change processes, it is well suited to the treatment of habitual and addictive behaviors. It has been successfully applied to addiction and substance use disorders. There have been countless books, articles, and evidence-based research studies on the Stages of Change. Its research base and application are so extensive that it has been a challenge to distill it to its simplest form for this post and for application with the Discovery Cards. Our objective is to give you the basics of the TTM and encourage you to seek out more information from the reference list included at the end of this post as well as other sources. We hope you will leverage what we provide below, explore the referenced resources, and add it as a model and tool for your work with individuals.

The Transtheoretical Model Definied

The Transtheoretical Model (TTM) is an integrative, biopsychosocial model used to conceptualize the process of intentional behavior change — that is, an individual’s readiness to act on new, healthier behavior. Whereas other models of behavior change focus on just one dimension of change (for example, they focus mainly on social factors, or psychological issues, or physical aspects), the TTM combines the most effective components from other theories into a comprehensive model of change. Its name spells out what it is: the prefix trans means across, and theoretical means concerned with the theory of a subject or area of study — hence, the term transtheoretical. The TTM has been applied successfully in a variety of behaviors, populations, and settings. The following four constructs of the TTM are required for progress toward recovery:

Stages of Change — the progression of stages through which individuals pass as they modify their behavior

Processes of Change — strategies to help individuals make and maintain change — the “how” of change

Decisional Balance — a growing awareness that the advantages (the “pros”) of changing outweigh the disadvantages (the “cons”)

Self-efficacy — confidence that one can make and maintain changes in situations that could trigger a return to previous unhealthy behaviors

We will briefly describe each of these four constructs of the TTM in more detail below:

1. Stages of Change Defined

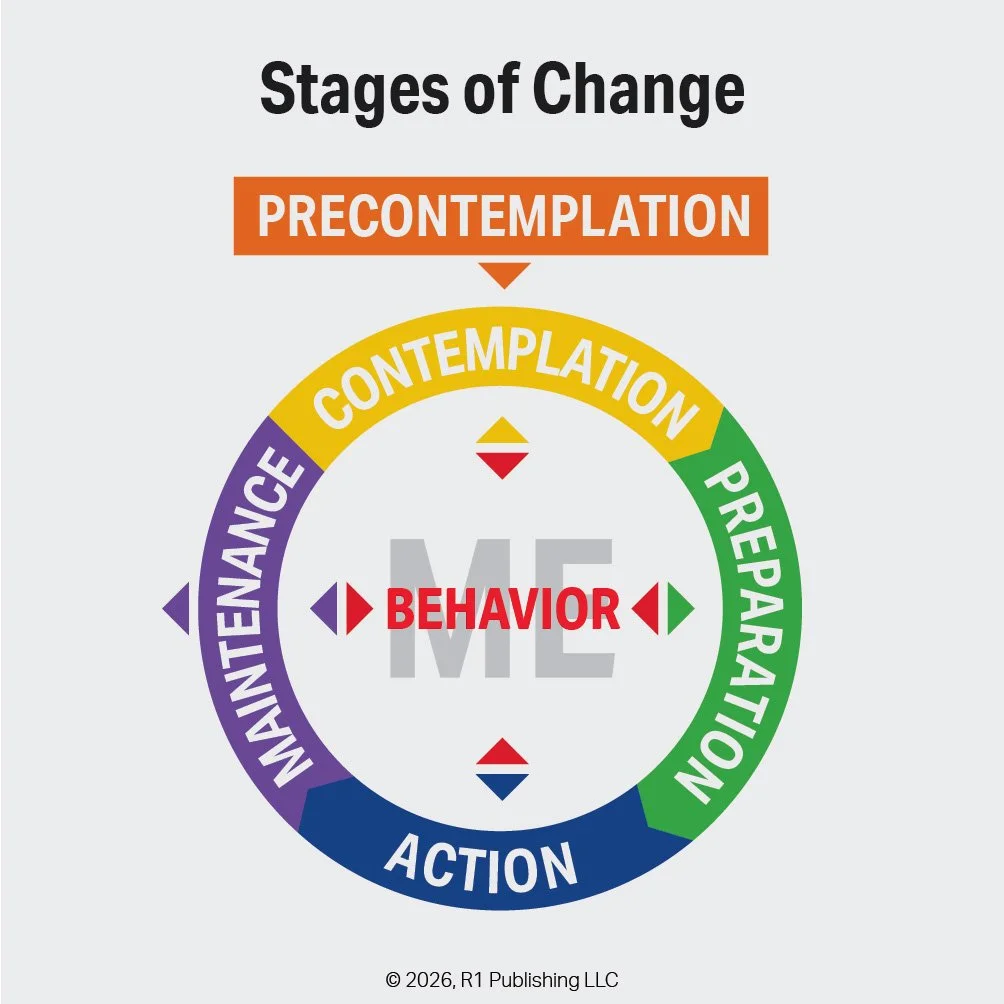

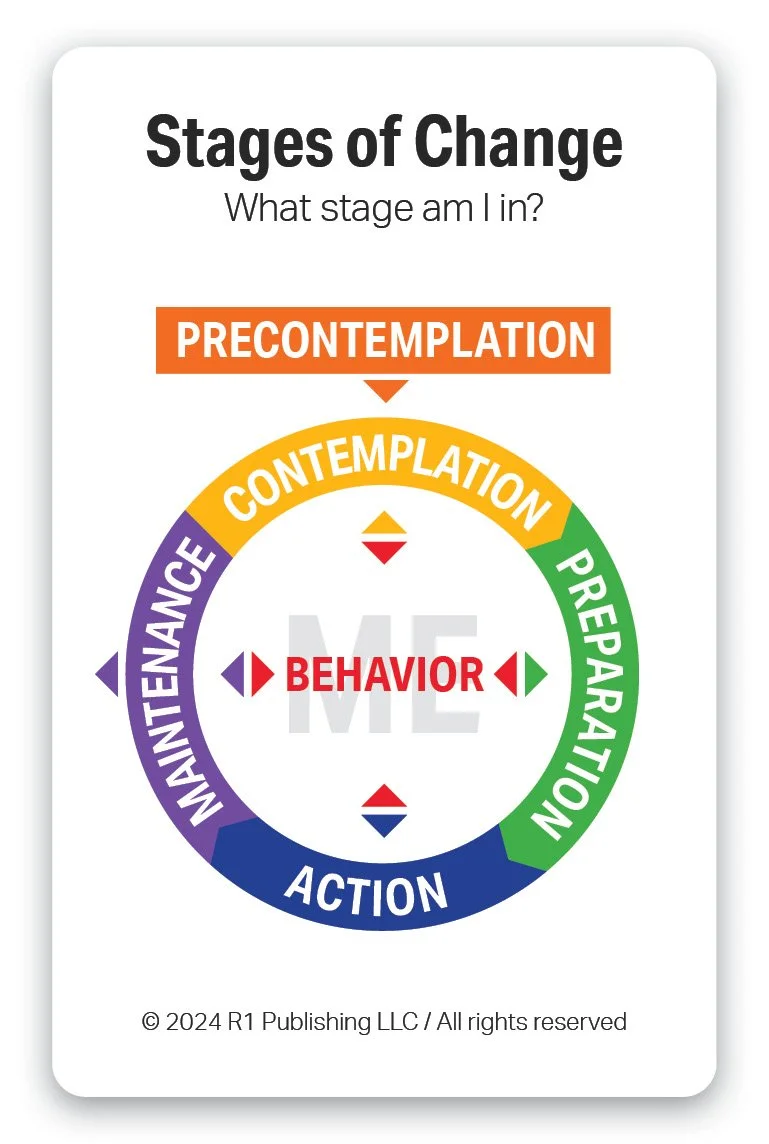

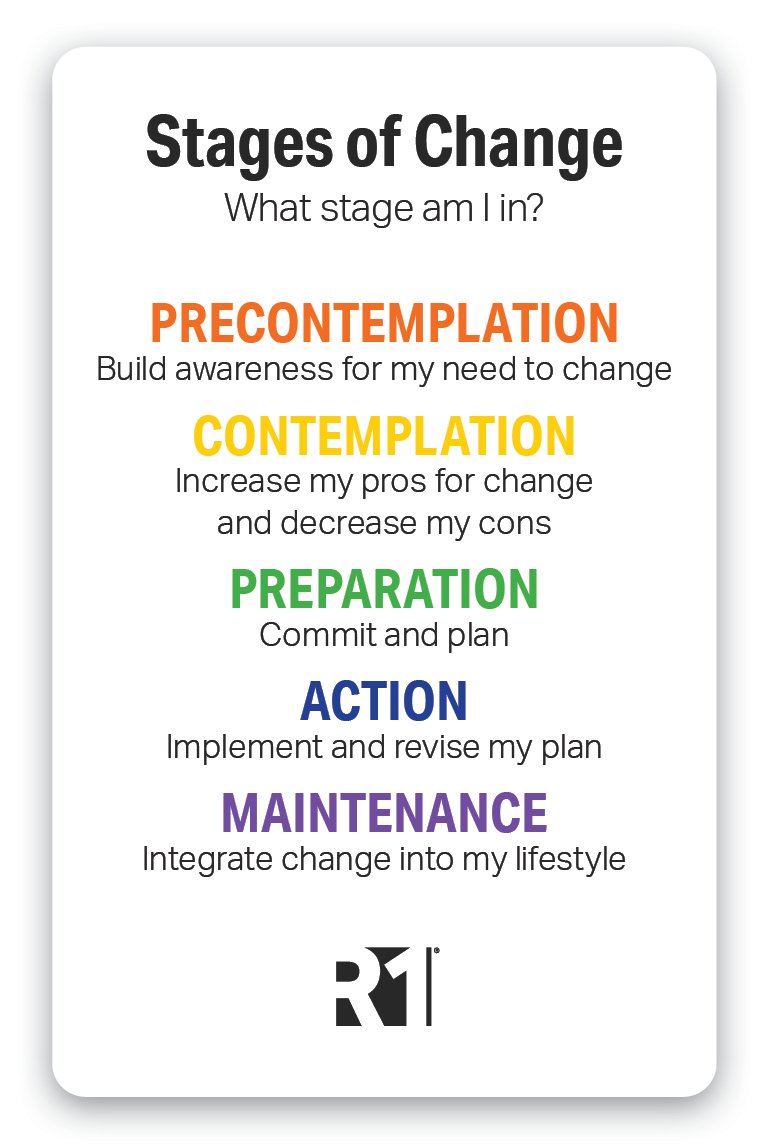

The TTM recognizes change as a process that unfolds over time, involving progress through a series of stages. According to the TTM, individuals move through a series of five stages — precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance — in the adoption of healthy behaviors or the cessation of unhealthy ones. These stages are defined below. While progression through the stages of change can occur in a linear fashion, a nonlinear progression is common.

Often, individuals recycle through the stages or regress to earlier stages from later ones. Although the time a person stays in each stage is variable, the tasks required to move to the next stage are not. Certain principles and processes of change come into play at each stage to reduce resistance, facilitate progress, and prevent relapse. Those principles include processes of change, decisional balance, and self-efficacy (more on these below). Only a minority (usually less than 20%) of at-risk individuals are prepared to take action toward change at any given time. As a result, action-oriented guidance can miss serve individuals in the early stages, as they may not be ready to take action. At each Stage of Change, there are specific intervention strategies that are most effective at helping the individual move to the next stage of change and subsequently through the model to the Maintenance Stage, which is the goal.

Individuals in the Precontemplation Stage do not intend to quit and start more healthy behavior in the near future (within 6 months) and may be unaware of the need to change. They typically underestimate the pros of changing, overestimate the cons, and are often not aware of this mindset. Individuals in this stage need to be more mindful of their decision-making and more conscious of the multiple benefits of changing their unhealthy behavior. Discovery Cards examples include:

I don’t think I could quit even if I wanted to

I don’t want to be told what to do regarding my drinking or using

I haven’t experienced any serious consequences as a result of my drinking or using

I really don’t see many benefits to quitting

Individuals in the Contemplation Stage intend to quit and start more healthy behavior within the next 6 months. While they are usually now more aware of the pros of changing, their cons are about equal to their pros. This ambivalence about changing can cause them to keep putting off taking action. Individuals in this stage learn about the benefits of change and the kind of person they could be if they quit and changed their behavior to more healthy ways. Discovery Cards examples include:

I see how my drinking or using can hurt others

I am noticing people who have quit and they seem healthier and happier

I think I may experience more serious consequences if I don’t quit soon

I think I might be healthier and happier if I quit

Individuals in the Preparation Stage are ready to start taking action within the next 30 days. They take small steps that they believe can help them quit and make the healthy behavior a part of their lives. It is helpful for individuals in this stage to seek support from friends they trust, tell people about their plan to change, and think about how they would feel if they behaved in a healthier way. Their number one concern is: When they act, will they fail? They learn that the better prepared they are, the more likely they are to keep progressing. Discovery Cards examples include:

I am planning ways to cut down or quit

I am seeking resources that will help me quit

I am ready to set a quit date

I believe that others will help me quit if I ask them to

Individuals in the Action Stage have changed their behavior within the last 6 months and need to work hard to keep progressing in recovery. Individuals in this stage need to learn how to strengthen their commitments to change and to fight urges to slip back that may cause them to relapse. They progress by learning to substitute activities related to the unhealthy behavior with positive ones, rewarding themselves for taking steps toward changing, and avoiding people, places, things, and situations that tempt them to behave in unhealthy ways. Discovery Cards examples include:

I am asking others for help

I am avoiding people, places, things, and situations that trigger me to drink or use

I am connecting with others and building a new network of sober friends

I am rewarding myself for quitting

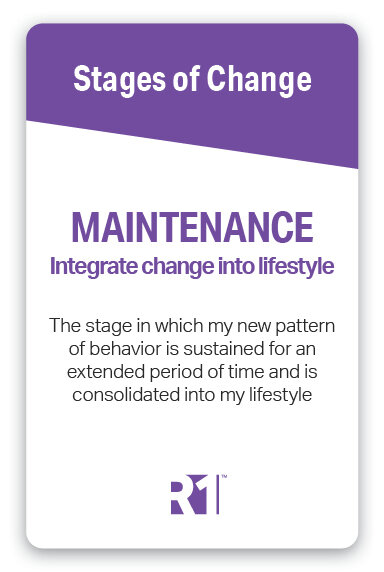

Individuals in the Maintenance Stage have changed their behavior for more than 6 months. It is important for people in this stage to be aware of situations that may tempt them to slip back into doing the unhealthy behavior — particularly stressful situations. Individuals in this stage are best served when they seek support from and talk with people whom they trust, spend time with people who behave in healthy ways, and remember to engage in healthy activities to cope with stress instead of relying on unhealthy behavior. Discovery Cards examples include:

I am going to continue to not drink or use — I enjoy sobriety

I am grateful for quitting and living a sober life

I am serving and supporting others in recovery

I have accepted that I am in recovery

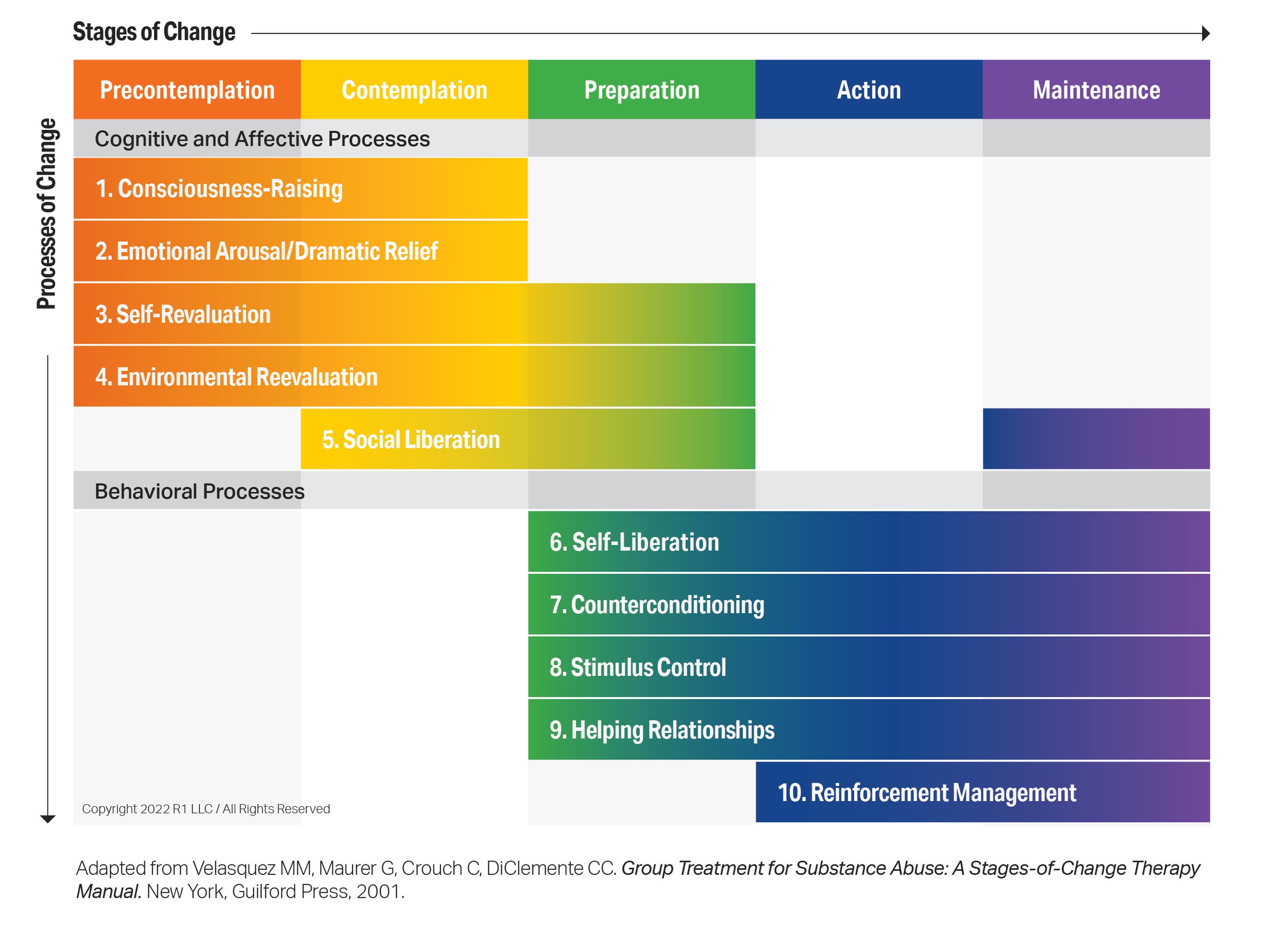

2. The Processes of Change Defined

While the Stages of Change are useful in explaining when changes in cognition, emotion, and behavior take place, the Processes of Change help to explain how those changes occur. These ten processes, which are defined below the table, can enable individuals to successfully progress through the Stages of Change when they attempt to modify problem behaviors and

attain desired behavior change. The Processes of Change can be divided into two groups: 1) cognitive and affective processes

and 2) behavioral processes. According to research on the TTM conducted by Drs. Prochaska and DiClemente and their

colleagues, interventions to change behavior are more effective if they are “stage-matched” — that is, interventional

techniques related to the specific processes are matched to the Stage of Change that individual is in. The table below

shows the Processes of Change matched to the Stages of Change, with color bars indicating the processes employed as

individuals move through stages.

Processes Matched to Stages - The Processes of Change employed by individuals to move through the Stages of Change

Consciousness-Raising — build awareness: Individuals increase awareness through information, education, and feedback about their current pattern and behavior, and/or their potential new behavior

Emotional Arousal / Dramatic Relief — pay attention to emotions and feelings: Individuals feel fear or anxiety because of their unhealthy behavior, or feel inspiration and hope when they hear about how people are able to change to new healthy patterns and behavior

Self-Reevaluation — create a new positive self-image: Individuals clarify values and realize that the new healthy pattern and behavior are an important part of who they are and aspire to be

Environmental Reevaluation — notice impact on others: Individuals realize how their unhealthy pattern and behavior negatively affect others and how they could have more positive effects by changing their behavior

Social Liberation — notice public support and gain alternatives: Individuals realize that society is more supportive of their new healthier behavior

Self-Liberation — make choices and commitments: Individuals believe in their ability to change and make choices, commitments, and re-commitments to act on their belief and stay the course in their recovery

Counterconditioning — use substitutes: Individuals substitute new healthy ways of thinking and acting for unhealthy patterns and behavior

Stimulus Control — observe and manage environment: Individuals use reminders and cues that encourage healthy behavior as substitutes for those that encourage unhealthy patterns and behavior

Helping Relationships — get help and support: Individuals find people who support their new healthy behavior

Reinforcement Management — use rewards: Individuals increase the rewards that come from positive healthy behavior and decrease those that come from negative unhealthy behavior

3. Decisional Balance Defined

Tipping the Balance Toward Change. When people make decisions, they weigh the costs and benefits of their different choices. Decision-making was conceptualized by Janis and Mann (1977) as a decisional “balance sheet” of potential gains and losses. Two components of decisional balance, the pros and the cons, have become core parts of the Transtheoretical Model (TTM). As individuals progress through the Stages of Change, decisional balance shifts in critical ways. When an individual is in the Precontemplation Stage, the pros for behavior change are outweighed by the cons, and the balance is in favor of maintaining the existing unhealthy behavior. In the Contemplation Stage, the pros and cons tend to carry equal weight, leaving the individual ambivalent about change. As the decisional balance is tipped such that the pros for changing outweigh the cons for maintaining the unhealthy behavior, many individuals move to the Preparation or even the Action Stage. As individuals enter the Maintenance Stage, the pros for maintaining the healthy behavior change should outweigh the cons of maintaining that change and thus decrease the risk of relapse.

4. Self-Efficacy Defined

Building Confidence Toward Change. Self-efficacy is a belief in our own competence to successfully accomplish a task and produce a favorable outcome. Self-efficacy plays a major role in determining one’s success — individuals with high self-efficacy are more likely to put forth sufficient effort that leads to successful outcomes; those with low self-efficacy are more likely to stop efforts early and fail. The TTM integrates elements of Bandura’s self-efficacy theory (Bandura 1977, 1982). This construct reflects the degree of confidence individuals have in maintaining their desired behavior change in situations that often trigger relapse. It is also measured by the degree to which individuals feel tempted to return to their problem behavior in high-risk situations. In the Precontemplation and Contemplation Stages, temptation to engage in the problem behavior is far greater than self-efficacy to abstain from that problem behavior. As individuals move from Preparation to Action, the disparity between feelings of self-efficacy and temptation closes, and behavior change is attained. Relapse often occurs in situations where feelings of temptation trump individuals’ sense of self-efficacy to maintain the desired behavior change.

Critical Assumptions of the TTM

The TTM is based on critical assumptions about the nature of behavior change and interventions that can best facilitate

such change:

Behavior change is a process that unfolds over time through a sequence of stages.

Stages are both stable and open to change, just as chronic behavior risk factors are both stable and open to change.

Interventions can motivate change by enhancing the understanding of the pros and diminishing the value of the cons.

Most at-risk individuals are not prepared for action and will not be served by traditional action-oriented prevention programs. Helping individuals set realistic goals, like progressing to the next stage, will facilitate the change process.

Specific principles and processes of change need to be matched with specific stages of change for progress through the stages to occur.

Copyright 2023 R1 Publishing LLC / All Rights Reserved. Use of this article for any purpose is prohibited without permission.

Questions to Explore

Answer these questions for yourself or someone you are working with.

Do you find this model helpful in thinking about your experience counseling / coaching clients with substance use?

Do the stages make sense to you? Are the categories helpful and easy to understand?

Which Discovery Cards behaviors resonate mostly with you as you read the examples?

As you look back over relevant counseling / coaching experiences, do you see how individuals move through the stages?

Do you see how individuals get stuck in certain stages? What keeps them stuck? How can you help them keep progressing through the stages?

How can you incorporate Motivational Interviewing (MI) techniques with the Stages of Change model and behaviors? What questions can you ask for each of the Discovery Card examples above when these behaviors show up?

How can you incorporate these ideas into your next one-on-one or group session?

The R1 Challenge: Thank you for reading this post and participating in this activity. How did you do? On a scale of 1 to 10, how would you rate your level of knowledge about this topic prior to reading our post? What is your level now? We hope you were able to walk away with at least one new learning or insight. Please share this post with your team and so they can test their knowledge too. Contact us if you would like to learn more about the Stages of Change Group Kits or the R1 Learning System. We look forward to hearing from you.

Facilitate Engaging Group Activities

Stages of Change Discovery Cards and Group Kits – Engagement Tools

Integrating these tools into your groups will allow individuals to build their own vocabulary, think about these concepts concretely, and put their choices into action. Visit the R1 Store to learn more about these evidence-based behavioral topics and models. The cards are an amazing tool for exploring these topics with individuals or groups.

References

Bandura A. “Self-Efficacy Mechanism in Human Agency.” American Psychologist 37:122–147, 1982.

Bandura A. “Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change.” Psychological Review 84:191–215, 1977.

DiClemente CC. Addiction and Change. New York, Guilford Press, 2018.

Janis IL, Mann L. Decision Making: A Psychological Analysis of Conflict, Choice, and Commitment. New York, Free Press, 1977.

Prochaska JO, Prochaska JM. Changing to Thrive. Center City, MN, Hazelden Publishing, 2016.

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. “In Search of How People Change: Applications to the Addictive Behaviors.” American Psychologist 47:1102–1114, 1992.

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. “Stages and Processes of Self Change of Smoking: Toward an Integrative Model of Change.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 51:390–395, 1983.

Velasquez MM, Maurer G, Crouch C, DiClemente CC. Group Treatment for Substance Abuse: A Stages-of-Change Therapy Manual. New York, Guilford Press, 2001.

Here are a few ideas to help you learn more about R1 and engage others on this topic:

Share this blog post with others. (Thank you!)

Start a conversation with your team. Bring this information to your next team meeting or share it with your supervisor. Change starts in conversations. Good luck! Let us know how it goes.

Visit www.R1LEARNING.com to learn more about R1, the Discovery Cards, and how we’re creating engaging learning experiences through self-discovery.