16 Evidence-based Practices — Do You Know the Basics?

And this post is going to be very basic. You’ll find it to be more of a list of terms, a glossary of sorts. What is considered evidence-based? What is adoption, adaption, and fidelity of practice? What are some of the most effective evidence-based practices being used today in substance use, addiction, and behavioral health programs?

Our purpose today is simple. We want to share the basic vocabulary in this learning space about evidence-base so that you and your organization will have a common language for reviewing, selecting, and implementing the most effective treatment, tools, and interventions for the communities you serve.

Evidence refers to information, facts, or data that support a claim or conclusion. Evidence is used to demonstrate that something is true or to justify decisions based on reliable observations or research.

So, what kind of evidence is required to be considered evidence-based? Sometimes the misconception is that the answer is binary… that a treatment or intervention of practice is either evidence-based or not. A deeper inquiry may include the question, “Where is it on the hierarchy of evidence?” and “Are there plans for this practice to gain more evidence and support for its effectiveness over time?” And for those innovative leading organizations… “Do we want to be part of a research study to enable this promising practice to move onto and up the hierarchy of evidence?”

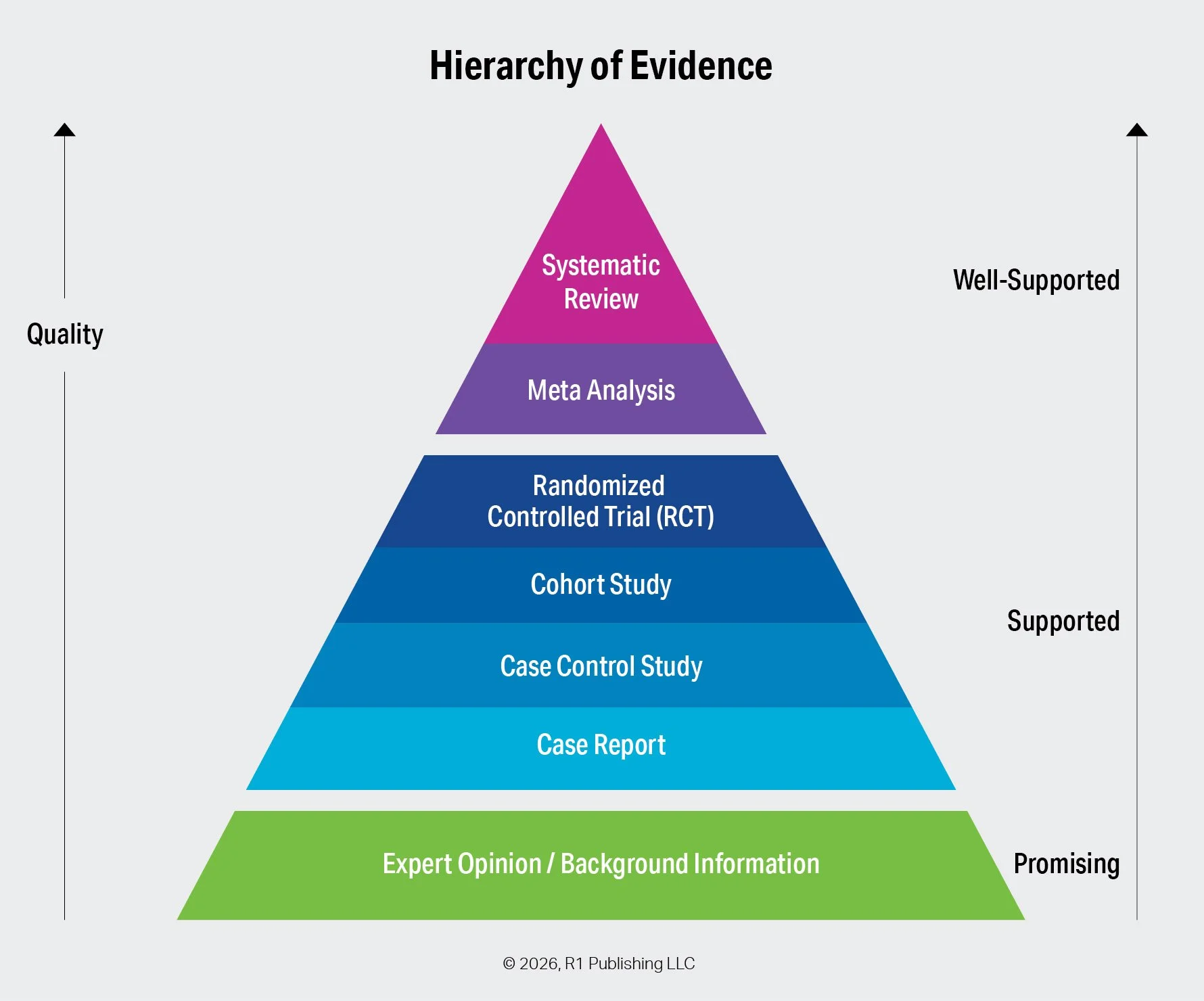

The Hierarchy of Evidence

Let’s start with the basics of how treatments, tools, and interventions become evidence-based over time. The primary types of evidence include the following, listed from highest to lowest strength:

Systematic Review – A systematic review comprehensively collects, evaluates, and synthesizes all relevant research on a specific practice, treatment, or intervention. Because it applies rigorous methods and critically appraises its sources, it is consistently ranked at the top of the evidence hierarchy.

Meta-Analysis – Often conducted as part of a systematic review, a meta-analysis statistically combines data from multiple studies. By aggregating results, it increases statistical power and produces conclusions that are more robust than those of individual studies. Its data-driven nature also helps reduce bias compared to purely observational research.

Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) – RCTs are structured experiments in which participants are randomly assigned to receive one of two or more interventions. Randomization minimizes selection bias and other sources of error. Although often placed just below systematic reviews and meta-analyses, some hierarchies rank RCTs at the highest level.

Cohort Study – A cohort study is an observational design in which researchers follow a group of participants who share a common characteristic and compare outcomes with a group that does not share that characteristic. Researchers observe outcomes without intervening.

Case-Control Study – In a case-control study, researchers compare individuals who have experienced a specific outcome (cases) with those who have not (controls). The groups are examined for prior exposure to potential risk factors. A higher exposure rate among cases suggests an association.

Case Report – A case report provides a detailed description of a single patient or a small group, including symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes. While considered lower-quality evidence due to limited sample size, case reports often serve as early indicators of emerging practices or effects.

Expert Opinion and Background Information – At the base of the evidence hierarchy are expert opinions and background sources. This category typically reflects professional consensus or guidelines issued by authoritative organizations rather than the views of a single individual.

Evidence-Based Practices Defined

Evidence-based practices (EVPs) refer to the treatments, tools, and interventions that have been scientifically tested and shown to be effective in improving outcomes via methods in the Hierarchy of Evidence above. These practices are grounded in research, clinical expertise, and client needs to ensure the best possible care. EVPs help providers and programs deliver consistent, high-quality support based on what has been proven to be effective.

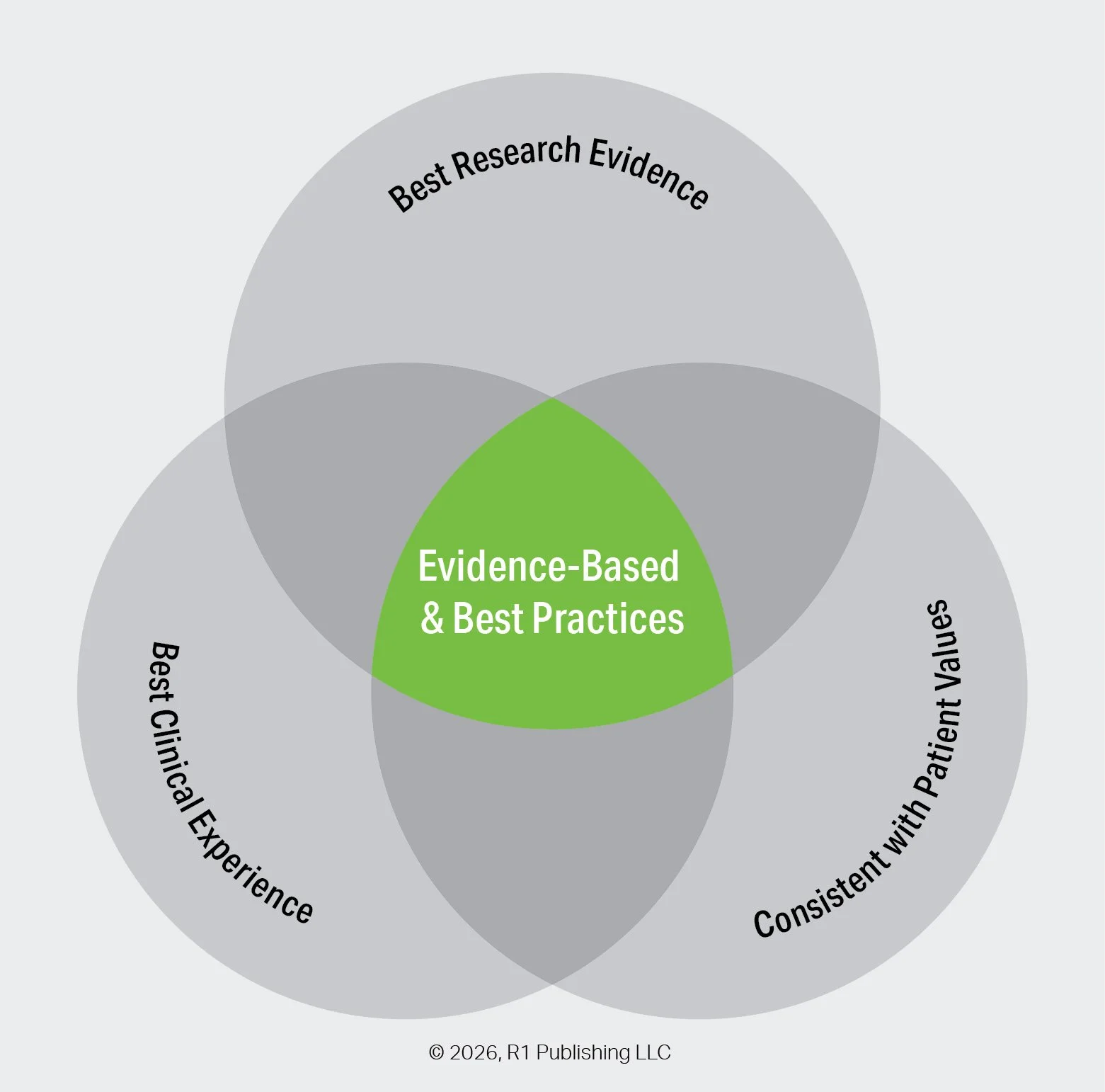

At The Intersection of Research, Experience, and Values

Evidence-based and best practices occur at the intersection of three equal considerations:

Best research evidence provides reliable findings from high-quality studies to inform what works.

Best clinical experience brings professional judgment and practical expertise gained through real-world practice.

Consistency with patient values ensures that decisions respect individual preferences, needs, and goals.

When these three elements are considered together, practices are more effective, appropriate, and meaningful.

Implementation of Evidence-based Practices

Implementing effective practices is one of the most important, and yet challenging, aspects for organizations, programs, and practitioners. What practices do we think will be most effective for the needs of our population and setting? How will we introduce, train, and empower our practitioners to be effective using these practices? Look for future posts on best practices for implementing evidence-based practices. In advance of these posts, here are a few of the terms most important to the implementation science of practice.

Fidelity of an evidence-based practice refers to the degree to which an intervention or program is delivered as it was originally designed and intended. It includes following the core components, procedures, and methods accurately to ensure the practice remains consistent with the evidence supporting it. High fidelity helps maximize the likelihood of achieving the expected outcomes.

Adoption of evidence-based practices refers to the process by which individuals, organizations, or systems decide to take up and begin using interventions or approaches that are supported by research evidence. It involves recognizing the value of the practice, making a commitment to implement it, and initiating steps to integrate it into routine care or service delivery. Adoption occurs after an evidence-based practice is selected but before it is fully implemented and sustained over time. In this way, adoption represents the critical early stage of moving research-supported practices into real-world settings.

Adaptation of evidence-based practices refers to the process of modifying or tailoring an intervention to better fit the needs, culture, resources, or context of a specific population or setting. These changes are made while aiming to preserve the core components responsible for the practice’s effectiveness. Adaptation helps ensure the intervention remains relevant and feasible in real-world implementation.

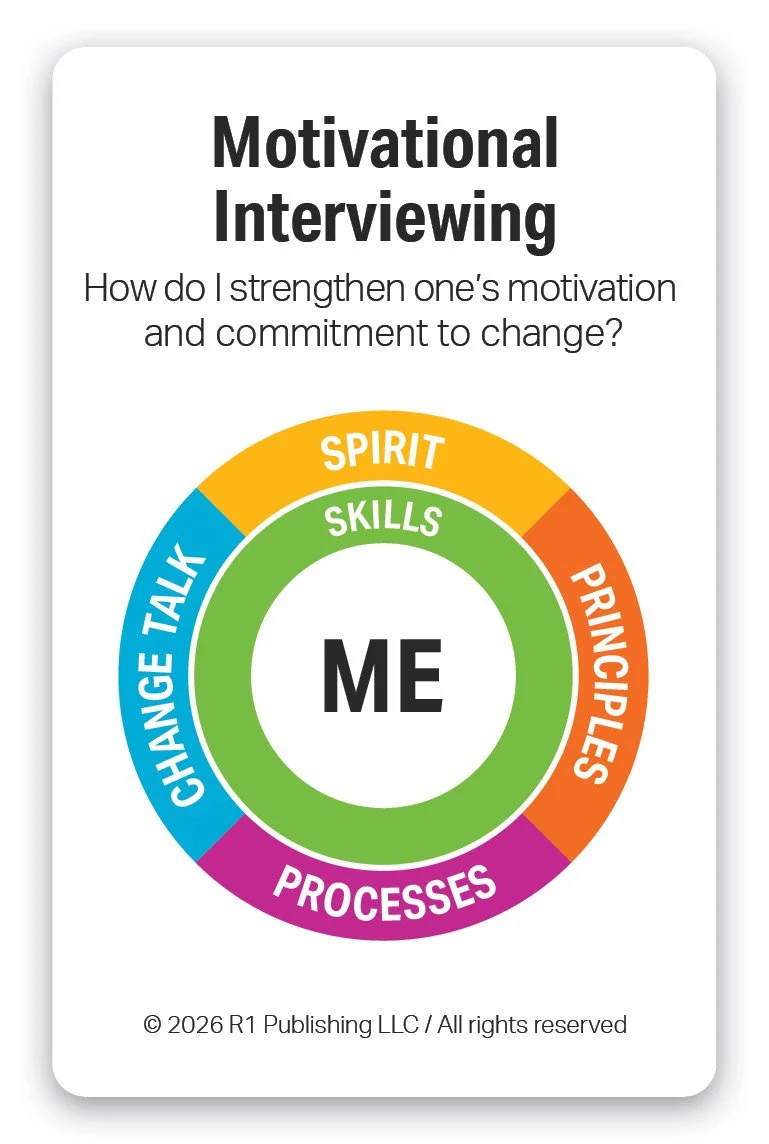

16 Evidence-Based Practices — Which Practices Do You Use?

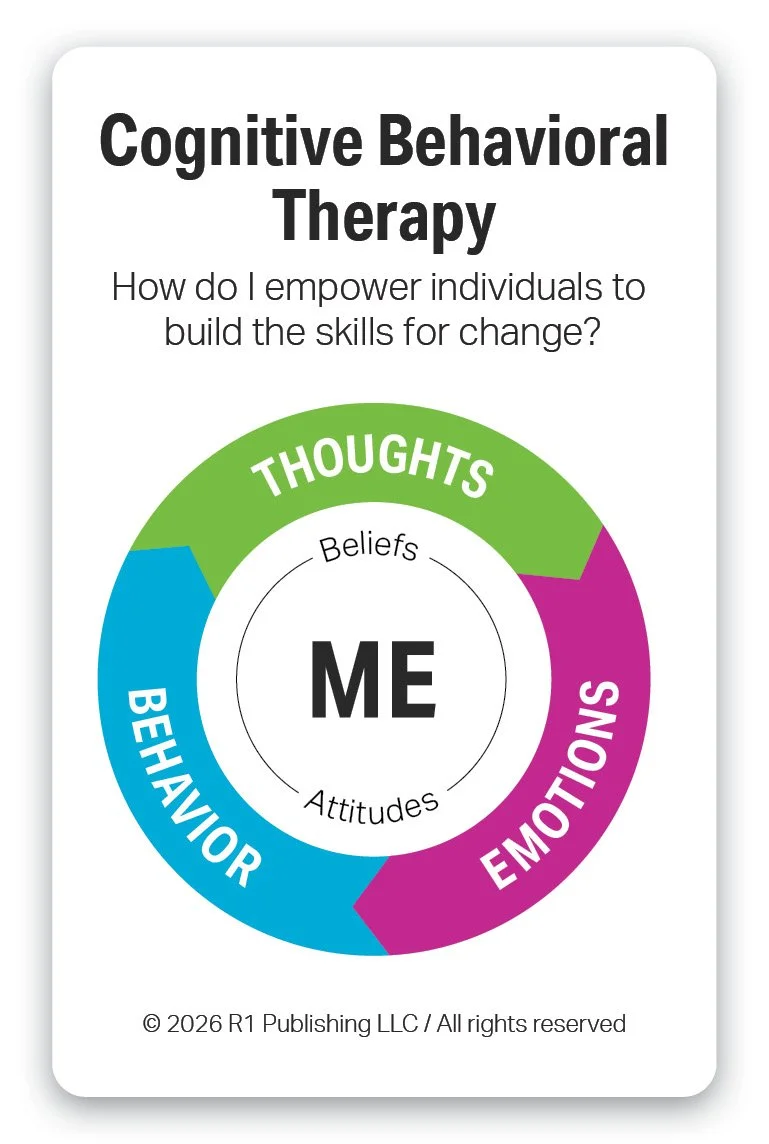

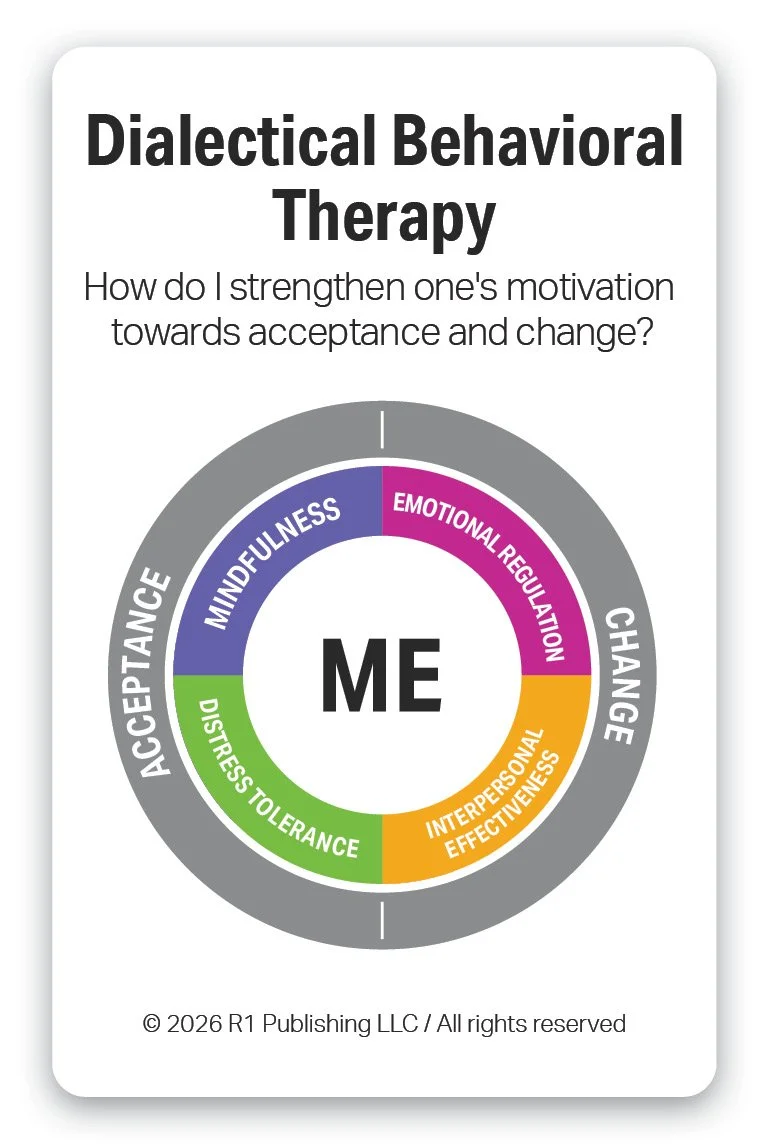

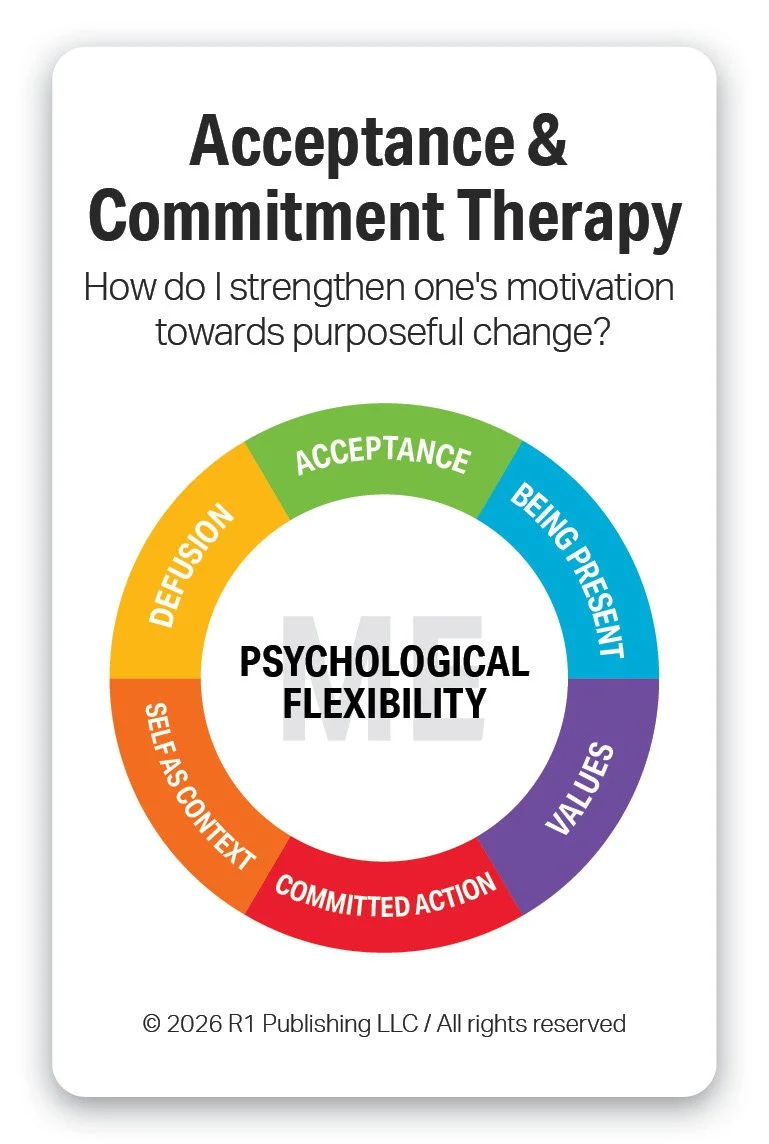

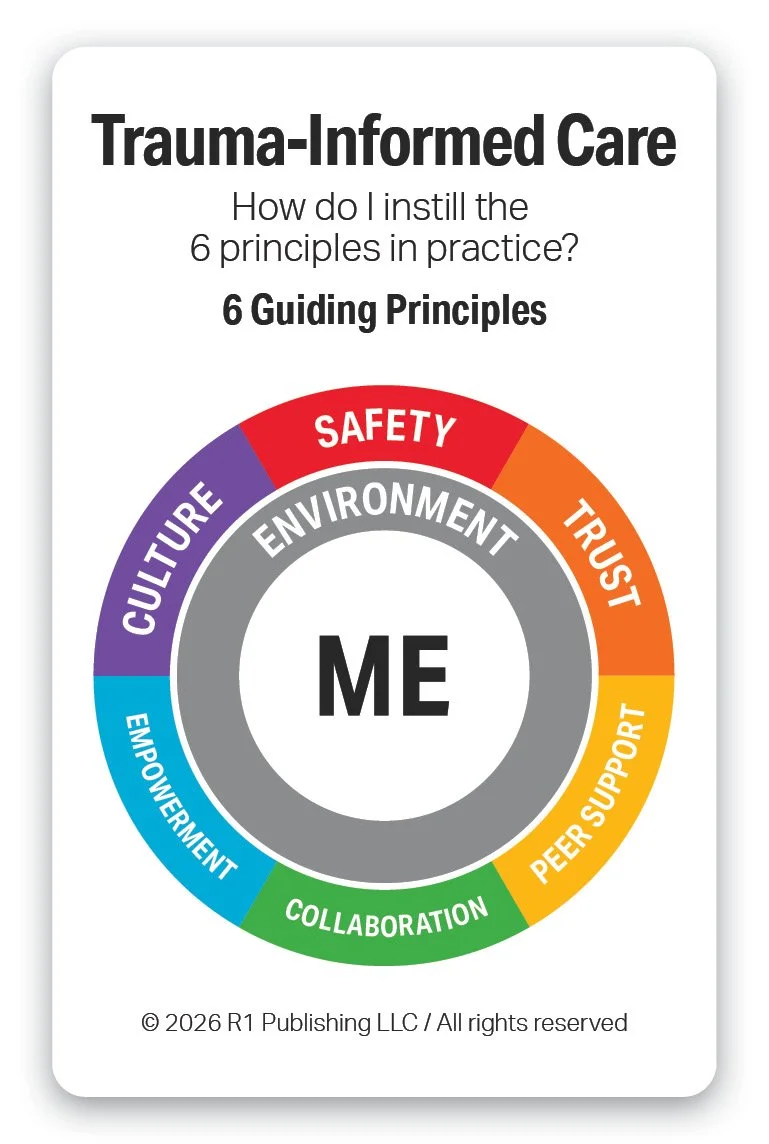

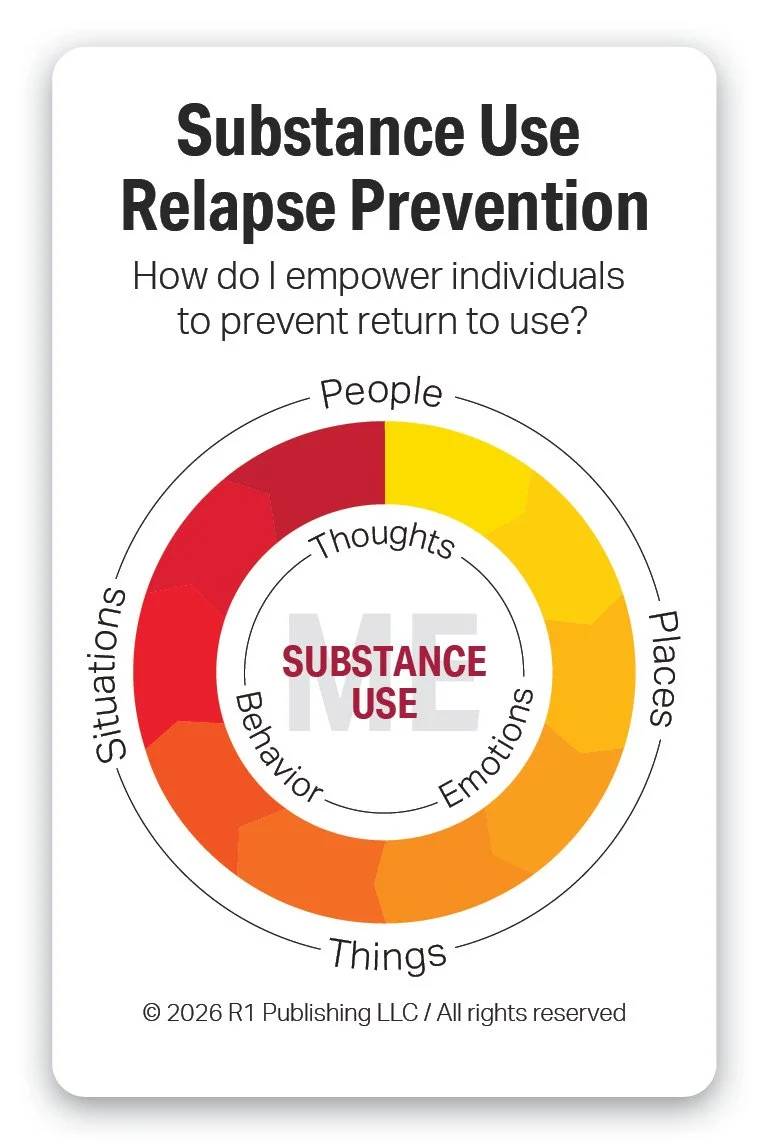

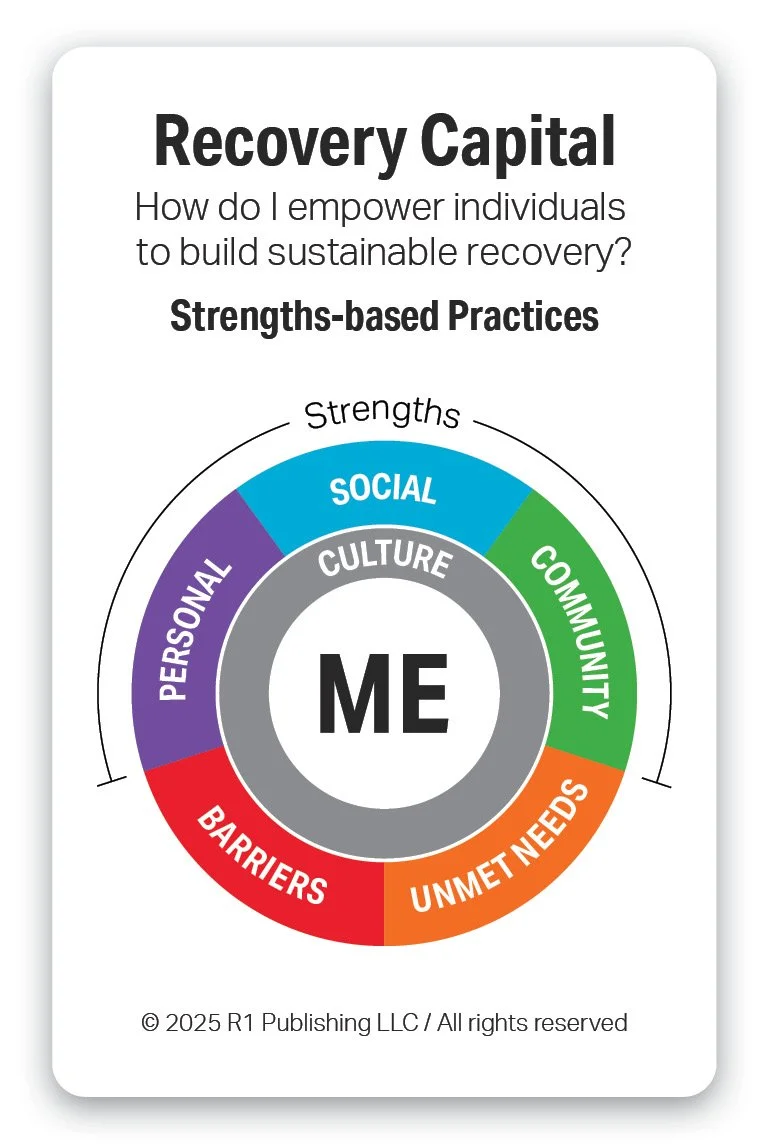

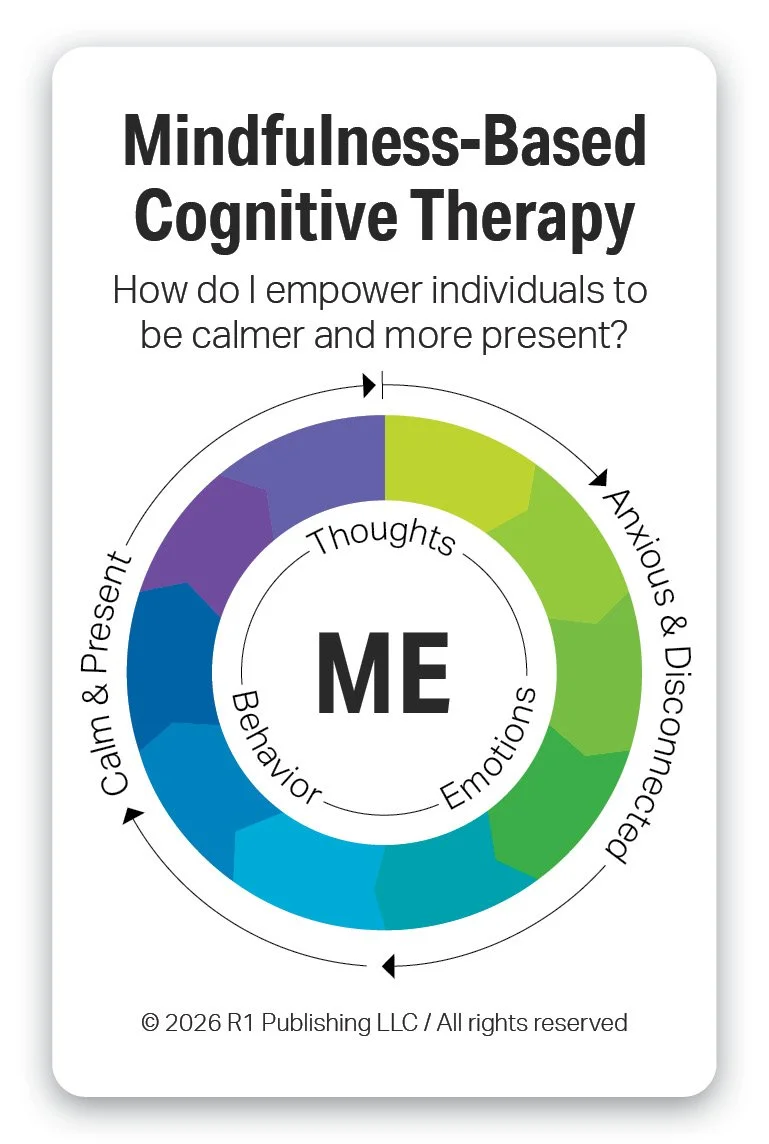

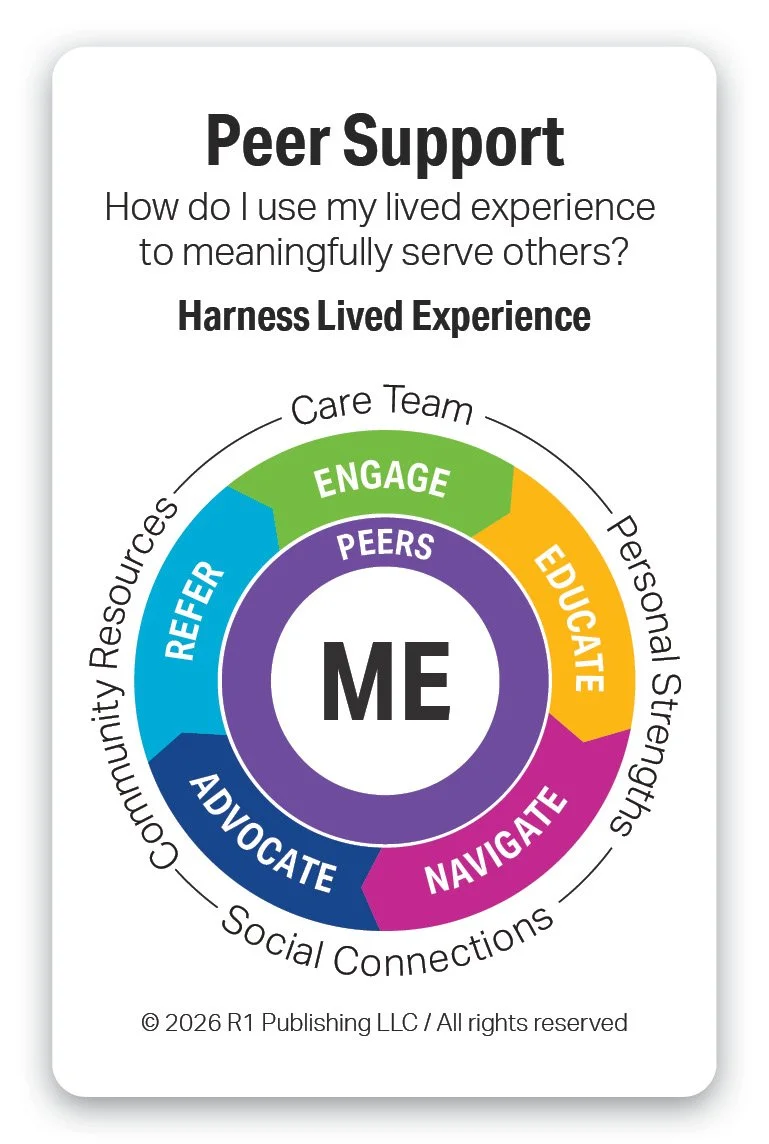

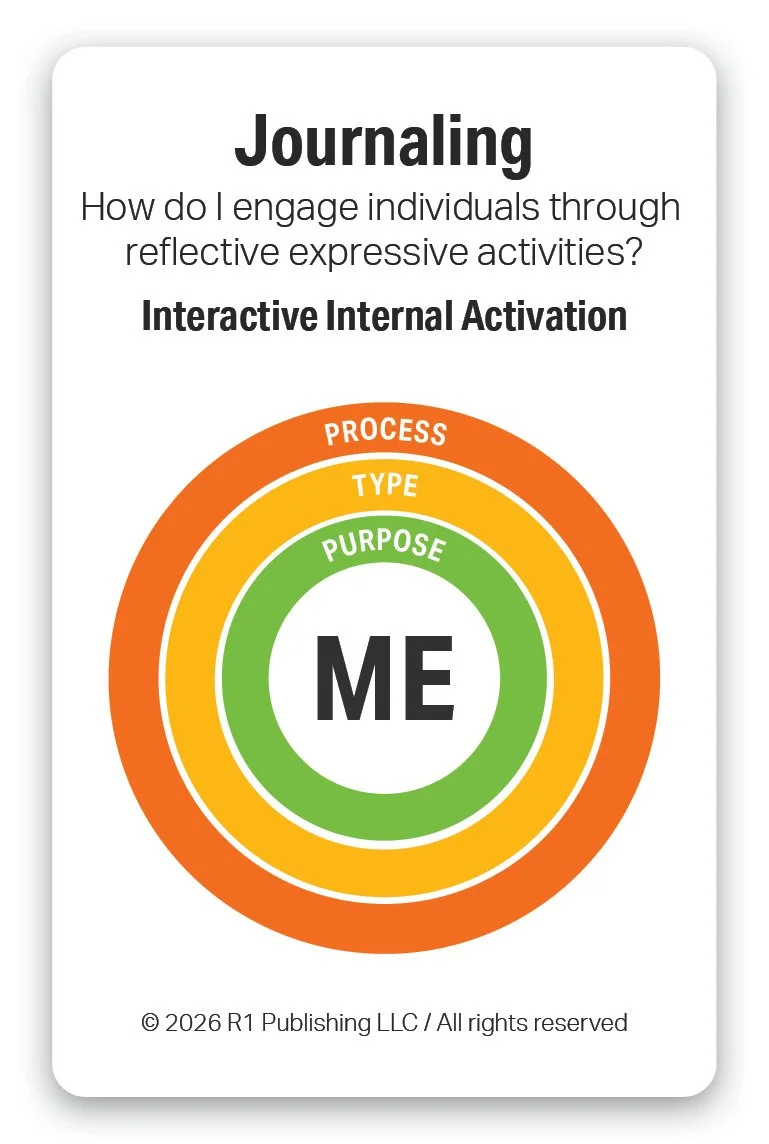

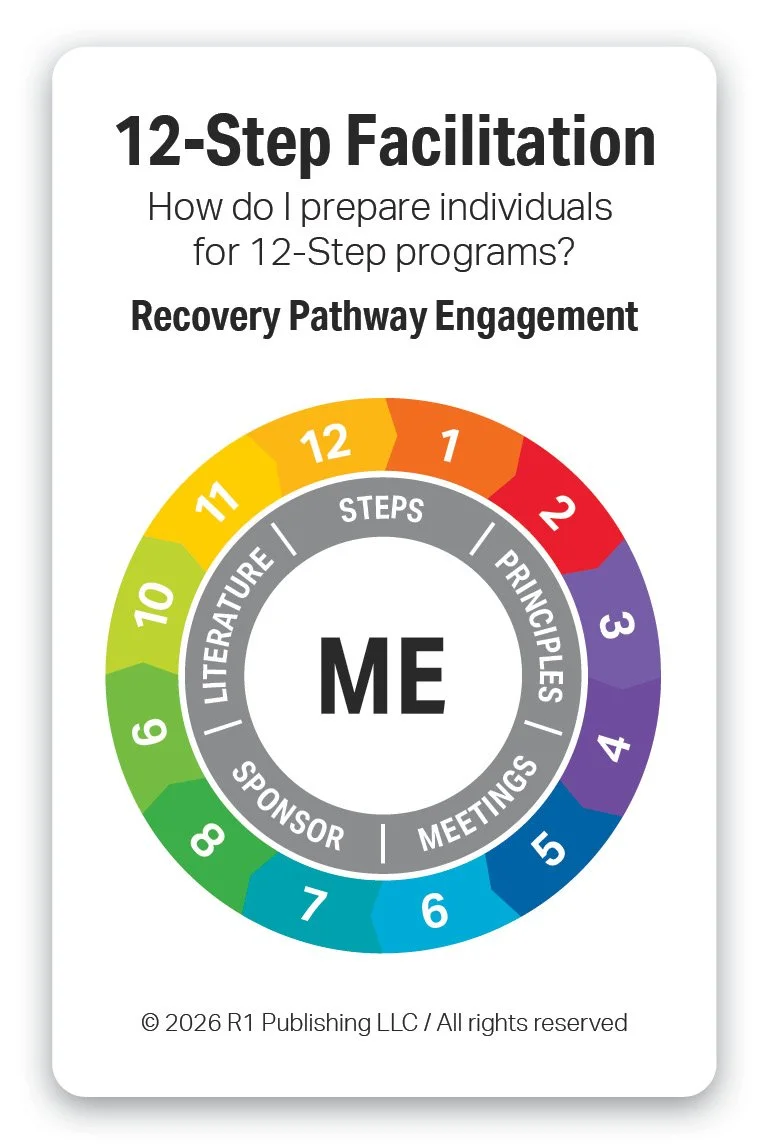

Lastly, below are a few of the most widely used evidence-based practices. Link here to learn the definition of each and how R1 Learning supports it. The list continues to evolve and grow, but these are a few of the most current tried-and-true ones. As you scan the list and models of practices, which ones do you use? Which ones do you find most effective and in what context? Which ones are you unfamiliar with? We hope R1’s visual models and questions for each engage you, stimulate your curiosity, inspire you to want to learn more, and prompt discussions within your organization.

Summary List: Motivational Interviewing (MI), Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT), Acceptance & Commitment Therapy (ACT), Trama-Informed Care (TIC), Substance Use/Relapse Prevention, Recovery Capital, Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy, Peer Support, Contingency Management, Group Therapy, Social Determinants of Health, Medication Assisted Treatment, Family Psychoeducation, Journaling, 12-Step Facilitation.

Others not shown in models above include The Transtheoretical Model & Stages of Change, Community Reinforcement Approach (CRA), Behavioral Activation (BA), Problem-Solving Therapy (PST), Gender Responsive Care, Digital Therapeutics, Eye Movement Desensitization and Processing (EMDR).

Questions to Explore

Answer the following questions for yourself or with your team:

What do you find most helpful about the Hierarchy of Evidence framework?

How will this information help you evaluate existing and emerging evidence-based treatments, tools, and interventions for your program? Explain.

Which of the 16 evidence-based practices do you use today? What have you found most helpful for each?

Which of the 16 evidence-based practices would you like to add to your practitioner toolkit as you build your professional knowledge, skill, and effectiveness?

What are some areas in your program where you can incorporate these practices?

What will be the benefit for you and others as you adopt and adapt these practices in your setting?

What is your major learning or takeaway from this post? Explain.

Thank you for reading this post and participating in this activity. Contact us if you would like to learn more about the R1 Learning System and our solutions. We look forward to hearing from you.

References

Sackett, D. L., Rosenberg, W. M. C., Gray, J. A. M., Haynes, R. B., & Richardson, W. S. (1996). Evidence based medicine: What it is and what it isn’t. BMJ, 312(7023), 71–72. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71

Sackett, D. L., Straus, S. E., Richardson, W. S., Rosenberg, W., & Haynes, R. B. (2000). Evidence-based medicine: How to practice and teach EBM (2nd ed.). Churchill Livingstone.

Guyatt, G., et al. (Eds.). (2015). Users' guides to the medical literature: A manual for evidence-based clinical practice (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

Straus, S. E., Glasziou, P., Richardson, W. S., & Haynes, R. B. (2019). Evidence-based medicine: How to practice and teach EBM (5th ed.). Elsevier.

Melnyk, B. M., & Fineout-Overholt, E. (2019). Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: A guide to best practice (4th ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

Melnyk, B. M., & Fineout-Overholt, E. (2022). Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: A guide to best practice (5th ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

LoBiondo-Wood, G., & Haber, J. (2022). Nursing research: Methods and critical appraisal for evidence-based practice (10th ed.). Mosby.

Higgins, J. P. T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M. J., & Welch, V. A. (Eds.). (2022). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119536604

Cochrane Library. (n.d.). Cochrane database of systematic reviews. Wiley Online Library

Copyright 2026 R1 Publishing LLC / All Rights Reserved. Use of this article for any purpose is prohibited without permission.

Here are a few ideas to help you learn more about R1 and engage others on this topic:

Share this blog post with others. (Thank you!)

Start a conversation with your team. Bring this information to your next team meeting or share it with your supervisor. Change starts in conversations. Good luck! Let us know how it goes.

Visit www.R1LEARNING.com to learn more about R1, the Discovery Cards, and how we’re creating engaging learning experiences through self-discovery.